Have you ever wondered WHY?

ANSWERS TO INTRIGUING QUESTIONs ABOUT JUDAISM

ANSWERS TO INTRIGUING QUESTIONs ABOUT JUDAISM

What is the holiday of Sukkot?

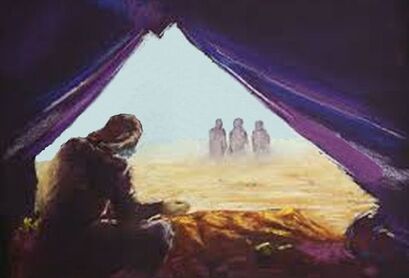

Sukkot is named after the booths or huts (Sukkot in Hebrew) in which traditionally observant Jews dwell during this week-long celebration. According to rabbinic tradition, these flimsy Sukkot represent the huts in which the Israelites dwelt during their 40 years of wandering in the desert after escaping from slavery in Egypt. The festival of Sukkot is one of the three great pilgrimage festivals (Regalim) of the Jewish year.

The origins of Sukkot are found in an ancient autumnal harvest festival. Indeed it is often referred to as hag ha-asif, “The Harvest Festival.” Much of the imagery and ritual of the holiday revolves around rejoicing and thanking God for the completed harvest. The sukkah represents the huts that farmers would live in during the last hectic period of harvest before the coming of the winter rains. Sukkot also commemorates the wanderings of the Israelites in the desert after the revelation at Mount Sinai, with the huts representing the temporary shelters that the Israelites lived in during those 40 years.

As soon after the conclusion of Yom Kippur as possible, often on the same evening, one is enjoined to begin building the sukkah, or hut, that is the central symbol of the holiday. The sukkah is a flimsy structure with at least three sides, whose roof is made out of thatch or branches, which provides some shade and protection from the sun, but also allows the stars to be seen at night. It is traditional to decorate the sukkah and to spend as much time in it as possible. Weather permitting, meals are eaten in the sukkah, and the hardier among us may also elect to sleep in the sukkah. In a welcoming ceremony called ushpizin, ancestors are symbolically invited to partake in the meals with us. And in commemoration of the bounty of the Holy Land, we hold and shake four species of plants (arba minim), consisting of palm, myrtle, and willow (lulav ), together with citron (etrog ). (Sourced in part from MyJewishLearning.com)

The origins of Sukkot are found in an ancient autumnal harvest festival. Indeed it is often referred to as hag ha-asif, “The Harvest Festival.” Much of the imagery and ritual of the holiday revolves around rejoicing and thanking God for the completed harvest. The sukkah represents the huts that farmers would live in during the last hectic period of harvest before the coming of the winter rains. Sukkot also commemorates the wanderings of the Israelites in the desert after the revelation at Mount Sinai, with the huts representing the temporary shelters that the Israelites lived in during those 40 years.

As soon after the conclusion of Yom Kippur as possible, often on the same evening, one is enjoined to begin building the sukkah, or hut, that is the central symbol of the holiday. The sukkah is a flimsy structure with at least three sides, whose roof is made out of thatch or branches, which provides some shade and protection from the sun, but also allows the stars to be seen at night. It is traditional to decorate the sukkah and to spend as much time in it as possible. Weather permitting, meals are eaten in the sukkah, and the hardier among us may also elect to sleep in the sukkah. In a welcoming ceremony called ushpizin, ancestors are symbolically invited to partake in the meals with us. And in commemoration of the bounty of the Holy Land, we hold and shake four species of plants (arba minim), consisting of palm, myrtle, and willow (lulav ), together with citron (etrog ). (Sourced in part from MyJewishLearning.com)

What is a Selichot service?

Selichot, prayers for forgiveness, are ancient prayers already mentioned in the Mishnah. They originated as prayers for fast days. The Mishnah describes public fast days and the order of prayer for such occasions as featuring a series of exhortations that end with the words “He will answer us,” recalling the times in Jewish history when God answered those who called upon Him. The Tanna debei Eliyahu Zuta, a midrashic work that dates at the latest to the ninth century, mentions a special service for forgiveness instituted by King David when he realized that the Temple would be destroyed.

“How will they attain atonement?” he asked the Lord and was told that the people would recite the order of Selichot and would then be forgiven. God even showed David that this act of contrition would include a recitation of the 13 Attributes of Mercy, a descriptive passage from Exodus that expresses God’s merciful nature.

The name “Lord” [the Hebrew letters YHWH which constitute God’s name] was consistently understood by the rabbis as referring to the appearance of God in His attribute of mercy. Therefore, its repetition in this passage indicated that God was merciful at all times.

The Selichot service also emphasizes the recitation of The 13 Attributes. Over the centuries, special poems embellishing this passage were added. The tradition of reciting Selichot throughout Elul, the month preceding Rosh Hashanah, may stem from the fact that it was customary to fast six days before Rosh Hashanah. Since the Selichot originated as prayers for fast days, it followed naturally that they would be recited at this time.

Sephardic communities begin reciting Selichot at the beginning of Elul so that a period of 40 days, similar to the time Moses spent on Mount Sinai, is devoted to prayers of forgiveness. The practice among Ashkenazi Jews is to begin saying them on the Saturday night prior to Rosh Hashanah.

Originally, Selichot prayers were recited early in the morning, prior to dawn. There was a custom in Eastern Europe that the person in charge of prayers would make the rounds of the village, knocking three times on each door and saying, “Israel, holy people, awake, arouse yourselves and rise for the service of the Creator!” It later became common practice to hold the first Selichot service — considered the most important — at a time more convenient for the masses of people. Therefore, the Saturday night service was moved forward to midnight. (BY RABBI DR. REUVEN HAMMER taken in part from MyJewishLearning.com)

“How will they attain atonement?” he asked the Lord and was told that the people would recite the order of Selichot and would then be forgiven. God even showed David that this act of contrition would include a recitation of the 13 Attributes of Mercy, a descriptive passage from Exodus that expresses God’s merciful nature.

The name “Lord” [the Hebrew letters YHWH which constitute God’s name] was consistently understood by the rabbis as referring to the appearance of God in His attribute of mercy. Therefore, its repetition in this passage indicated that God was merciful at all times.

The Selichot service also emphasizes the recitation of The 13 Attributes. Over the centuries, special poems embellishing this passage were added. The tradition of reciting Selichot throughout Elul, the month preceding Rosh Hashanah, may stem from the fact that it was customary to fast six days before Rosh Hashanah. Since the Selichot originated as prayers for fast days, it followed naturally that they would be recited at this time.

Sephardic communities begin reciting Selichot at the beginning of Elul so that a period of 40 days, similar to the time Moses spent on Mount Sinai, is devoted to prayers of forgiveness. The practice among Ashkenazi Jews is to begin saying them on the Saturday night prior to Rosh Hashanah.

Originally, Selichot prayers were recited early in the morning, prior to dawn. There was a custom in Eastern Europe that the person in charge of prayers would make the rounds of the village, knocking three times on each door and saying, “Israel, holy people, awake, arouse yourselves and rise for the service of the Creator!” It later became common practice to hold the first Selichot service — considered the most important — at a time more convenient for the masses of people. Therefore, the Saturday night service was moved forward to midnight. (BY RABBI DR. REUVEN HAMMER taken in part from MyJewishLearning.com)

What is the significance of the 18th day of Elul?

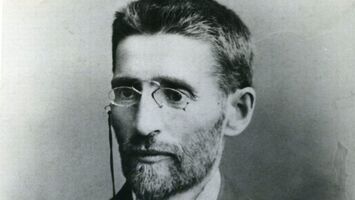

"Chai Elul", the 18th day of the Hebrew month of Elul, is a most significant date, especially for Chassidic Jews. The founder of Chassidism, Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov, was born on this date, in 1698. It is also the day, 36 years later, on which the Baal Shem Tov began to publicly disseminate his groundbreaking teachings, after many years as a member of the society of "hidden tzaddikim", during which he lived disguised as a simple innkeeper and clay-digger, his greatness known only to a very small circle of fellow mystics and disciples.

The numerical value of the Hebrew word Chai, which means life, is 18. Therefore for example, it is customary for Jews to make donations in multiples of 18, as well as recognize calendar dates including the number 18 as especially auspicious.

Elul 18 is also the birthday, in 1745, of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, who often referred to himself as the Baal Shem Tov's "spiritual grandson". He was also known as the “Alter Rebbe”, Yiddish for the old Rebbe.

After gaining fame as a child prodigy and young Talmudic genius, Rabbi Schneur Zalman journeyed to Mezeritch to study under the tutelage of the Baal Shem Tov's successor, Rabbi Dov Ber also knows as the Maggid of Mezeritch. As the Alter Rebbe later explained, "to study I knew somewhat, but I needed to learn how to pray", and was soon accepted into the intimate circle of Rabbi Dov Ber's leading disciples.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman established the "Chabad" branch of Chassidism, which till this day emphasizes in-depth study and intense contemplation as the key to vitalizing the entire person, from sublime mind to practical deed. (Sourced in part from Chabbad.org)

The numerical value of the Hebrew word Chai, which means life, is 18. Therefore for example, it is customary for Jews to make donations in multiples of 18, as well as recognize calendar dates including the number 18 as especially auspicious.

Elul 18 is also the birthday, in 1745, of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, who often referred to himself as the Baal Shem Tov's "spiritual grandson". He was also known as the “Alter Rebbe”, Yiddish for the old Rebbe.

After gaining fame as a child prodigy and young Talmudic genius, Rabbi Schneur Zalman journeyed to Mezeritch to study under the tutelage of the Baal Shem Tov's successor, Rabbi Dov Ber also knows as the Maggid of Mezeritch. As the Alter Rebbe later explained, "to study I knew somewhat, but I needed to learn how to pray", and was soon accepted into the intimate circle of Rabbi Dov Ber's leading disciples.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman established the "Chabad" branch of Chassidism, which till this day emphasizes in-depth study and intense contemplation as the key to vitalizing the entire person, from sublime mind to practical deed. (Sourced in part from Chabbad.org)

Why is romantic love an Elul theme?

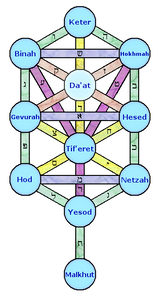

We are in the Hebrew month of Elul, the letters of whose name famously form an acronym for the phrase ani l’dodi v’dodi li — I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine.

This phrase comes from Song of Songs (6:3), a poetic back and forth between a male and female each longing for the other’s love. The rabbis classically interpreted Song of Songs as an allegory for the on-again, off-again romance between God and the Jewish people.

We do find images of God as lover elsewhere in Jewish tradition, perhaps most notably in the Friday night liturgy. This is where a theology of hieros gamos, or sacred union, is most pronounced, as we welcome the transcendent God to cohabit with the Shabbat queen on earth, an immanent face of the manifest divine. But notwithstanding the long history of ecstatic poetry, from King Solomon’s palace through to the Renaissance mystics, in general Judaism has not organized itself around the sense of God as lover. Far more standard are images of God as king, father and creator.

Even if these conceptions of God are intended as benevolent, they are still fundamentally hierarchical. The king is in charge, and father knows best. Creator, father and king all imply a singular power, distinct from the many millions of its multifarious progeny. Unlike the unique intimacy of a beloved, these images are apt to make our deity feel rather impersonal and remote. How much individual attention can we really expect from a father whose living human children alone number more than eight billion?

And where God is depicted as a husband or romantic partner in Jewish tradition, the implications are frequently disturbing. In his extensive use of the “faithless wife” analogy, the prophet Hosea fulminates against Israel’s adulterous attraction to other gods, an infidelity that leaves “her” legitimately deserving of violent punishment. The Book of Lamentations expresses this violence outright, drawing explicit focus to the disgraced body of Zion. She is seen not merely weeping, humiliated and scorned by her former friends, but even coded as the victim of sexual violence — “snatched at,” “raped,” “her nakedness exposed,” “with unclean blood clinging to her skirts.”

Constructing the encompassing body of the nation as female (along with ships and sports teams) is not limited to Jews, and in fact is common in the wider culture. However, the Hebrew language also genders not only soul (neshamah) but self (nefesh) in the feminine. Relative to the penetrating presence of divine life-force, the containing receptacle of each individual is “female,” regardless of biological sex. At some level, this is presumably a human projection of our reproductive mechanism onto the mystery of existence: If matter is mother, some tiny animating spark of encoded intelligence from the great Other is still needed to seed creation.

Gender, then, is metaphor — in the deeper sense of the word: a splitting into parts. For as Deuteronomy 4:35 reminds us, at root “there is nothing else but God.” The supposed duality of lover and beloved must therefore be mere playfulness, a contraction of the all-pervasive Self-awareness of God precisely so that It might experience the delight of being found and known and merged with once again.

A famous midrash (Bereishit Rabbah 8:1) understands the description in Genesis of humanity’s creation as an account of primordial man and woman being separated out from one original androgynous body. This separation, say the rabbis, lets us go from being whole but unconscious of our wholeness to being able to approach one another face to face, panim el panim. It is only thus that we can see the presence of God in one another — and find ourselves as both lover and beloved, rooted into the cosmos by the experience of love itself.

And in that love we might well find that as much as I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine, at heart I am my beloved, and My Beloved Is Me. (BY KOHENET RABBI SARAH BRACHA GERSHUNY and found in MyJewishLearning.com)

This phrase comes from Song of Songs (6:3), a poetic back and forth between a male and female each longing for the other’s love. The rabbis classically interpreted Song of Songs as an allegory for the on-again, off-again romance between God and the Jewish people.

We do find images of God as lover elsewhere in Jewish tradition, perhaps most notably in the Friday night liturgy. This is where a theology of hieros gamos, or sacred union, is most pronounced, as we welcome the transcendent God to cohabit with the Shabbat queen on earth, an immanent face of the manifest divine. But notwithstanding the long history of ecstatic poetry, from King Solomon’s palace through to the Renaissance mystics, in general Judaism has not organized itself around the sense of God as lover. Far more standard are images of God as king, father and creator.

Even if these conceptions of God are intended as benevolent, they are still fundamentally hierarchical. The king is in charge, and father knows best. Creator, father and king all imply a singular power, distinct from the many millions of its multifarious progeny. Unlike the unique intimacy of a beloved, these images are apt to make our deity feel rather impersonal and remote. How much individual attention can we really expect from a father whose living human children alone number more than eight billion?

And where God is depicted as a husband or romantic partner in Jewish tradition, the implications are frequently disturbing. In his extensive use of the “faithless wife” analogy, the prophet Hosea fulminates against Israel’s adulterous attraction to other gods, an infidelity that leaves “her” legitimately deserving of violent punishment. The Book of Lamentations expresses this violence outright, drawing explicit focus to the disgraced body of Zion. She is seen not merely weeping, humiliated and scorned by her former friends, but even coded as the victim of sexual violence — “snatched at,” “raped,” “her nakedness exposed,” “with unclean blood clinging to her skirts.”

Constructing the encompassing body of the nation as female (along with ships and sports teams) is not limited to Jews, and in fact is common in the wider culture. However, the Hebrew language also genders not only soul (neshamah) but self (nefesh) in the feminine. Relative to the penetrating presence of divine life-force, the containing receptacle of each individual is “female,” regardless of biological sex. At some level, this is presumably a human projection of our reproductive mechanism onto the mystery of existence: If matter is mother, some tiny animating spark of encoded intelligence from the great Other is still needed to seed creation.

Gender, then, is metaphor — in the deeper sense of the word: a splitting into parts. For as Deuteronomy 4:35 reminds us, at root “there is nothing else but God.” The supposed duality of lover and beloved must therefore be mere playfulness, a contraction of the all-pervasive Self-awareness of God precisely so that It might experience the delight of being found and known and merged with once again.

A famous midrash (Bereishit Rabbah 8:1) understands the description in Genesis of humanity’s creation as an account of primordial man and woman being separated out from one original androgynous body. This separation, say the rabbis, lets us go from being whole but unconscious of our wholeness to being able to approach one another face to face, panim el panim. It is only thus that we can see the presence of God in one another — and find ourselves as both lover and beloved, rooted into the cosmos by the experience of love itself.

And in that love we might well find that as much as I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine, at heart I am my beloved, and My Beloved Is Me. (BY KOHENET RABBI SARAH BRACHA GERSHUNY and found in MyJewishLearning.com)

Why blow Shofar during the month of Elul?

Because there is so much at stake spiritually during Rosh Hashanah, we make preparations beginning a full month earlier. At Rosh Hodesh Elul , or the start of the new month of Elul, we begin to stir with anticipation for this day of spiritual renewal. The most prominent feature of the month of Elul is the sounding of the shofar each morning, except on Shabbat. Three primary reasons are given for this practice.

The first one is to confuse Satan about the date for Rosh Hashanah, so that he will not be able to affect God’s judgment of people with his accusations against them.

The second one pertains to a rabbinic legend, which says that Moses’ ascent to receive the second tablets on the first of Elul was accompanied by blasts of the shofar. Therefore, the shofar reminds us of the story of the Golden Calf and that we must always be aware of our potential for sinning.

The third one has as its source the famous phrase heard at many weddings from the Song of Songs (6:3) Ani l’dodi v’dodi li, meaning “, I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine.” The first letters (aleph, lamed, vav, lamed) of each Hebrew word form an acrostic for the word "Elul" אלול. From this hint, we gather that the period extending from the beginning of Elul through Yom Kippur (a total of 40 days) is a time ripe to become beloved by God, and relearn the delicate art of loving God. The shofar alerts us to that love relationship. (By RABBI PAUL STEINBERG, sourced in part from MyJewishLearning.com)

The first one is to confuse Satan about the date for Rosh Hashanah, so that he will not be able to affect God’s judgment of people with his accusations against them.

The second one pertains to a rabbinic legend, which says that Moses’ ascent to receive the second tablets on the first of Elul was accompanied by blasts of the shofar. Therefore, the shofar reminds us of the story of the Golden Calf and that we must always be aware of our potential for sinning.

The third one has as its source the famous phrase heard at many weddings from the Song of Songs (6:3) Ani l’dodi v’dodi li, meaning “, I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine.” The first letters (aleph, lamed, vav, lamed) of each Hebrew word form an acrostic for the word "Elul" אלול. From this hint, we gather that the period extending from the beginning of Elul through Yom Kippur (a total of 40 days) is a time ripe to become beloved by God, and relearn the delicate art of loving God. The shofar alerts us to that love relationship. (By RABBI PAUL STEINBERG, sourced in part from MyJewishLearning.com)

What is the significance of Elul?

This Jewish month marks the period of soul-searching leading up to the High Holidays.

Although the month of Elul — the sixth month of the Jewish year, which immediately precedes Rosh Hashanah — has no special importance in the Bible or in early rabbinic writings, various customs arose sometime during the first millennium that designated Elul as the time to prepare for the High Holy Days. Because these days are filled with so much meaning and potency, they require a special measure of readiness. We are called upon to enter them thoughtfully and to consider what they mean. As the Maharal of Prague said, “All the month of Elul, before eating and sleeping, a person should look into his soul and search his deeds, that he may make confession.”

Jewish tradition points to the name of the month as symbolically appropriate. The letters of Elul form an acronym for the words in the verse Ani le‑dodi ve‑dodi li–“I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine” (Song of Songs 6:3). Believing that the “beloved” refers to God, the sages take this verse to describe the particularly loving and close relationship between God and Israel. Elul, then, is our time to establish this closeness so that we can approach the Yamim Noraim, or Days of Awe, in trusting acceptance of God’s judgment. We approach the trial not out of fear, but out of love. (By Rabbi Reuven Hammer, Ph.D in theology from the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. He teaches Jewish studies and special education in Jerusalem. Sourced in part from myJewishlearning.com)

Although the month of Elul — the sixth month of the Jewish year, which immediately precedes Rosh Hashanah — has no special importance in the Bible or in early rabbinic writings, various customs arose sometime during the first millennium that designated Elul as the time to prepare for the High Holy Days. Because these days are filled with so much meaning and potency, they require a special measure of readiness. We are called upon to enter them thoughtfully and to consider what they mean. As the Maharal of Prague said, “All the month of Elul, before eating and sleeping, a person should look into his soul and search his deeds, that he may make confession.”

Jewish tradition points to the name of the month as symbolically appropriate. The letters of Elul form an acronym for the words in the verse Ani le‑dodi ve‑dodi li–“I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine” (Song of Songs 6:3). Believing that the “beloved” refers to God, the sages take this verse to describe the particularly loving and close relationship between God and Israel. Elul, then, is our time to establish this closeness so that we can approach the Yamim Noraim, or Days of Awe, in trusting acceptance of God’s judgment. We approach the trial not out of fear, but out of love. (By Rabbi Reuven Hammer, Ph.D in theology from the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. He teaches Jewish studies and special education in Jerusalem. Sourced in part from myJewishlearning.com)

What is the latest with Israel's judicial coup? Is there hope?

When Israel’s parliament on Monday passed the first plank in a series of reform proposals meant to curb the power of Israel’s judiciary, it set off alarms among Israel’s supporters abroad.

Rabbi Donniel Hartman is urging critics of the judicial reforms and Netanyahu’s government to take a deep breath. Not because he supports the proposals — he agrees they would “undermine the systems of checks and balances necessary to protect Israel’s democratic identity.” But he warns that the bill passed on Monday represents one of the least controversial planks in Netanyahu’s reform plan, and that the massive demonstrations against the proposals have united an Israeli consensus around what he is calling a “new social coalition.”

An interview with Rabbi Donniel Hartman:

Carol: I’ve been thinking of the “day after” fear and anticipation after some recent watershed events – Trump’s election, the Dobbs decision that overturned Roe v. Wade, maybe the Brexit vote. Did Monday’s vote on the “reasonableness” clause mark a before and after?

Hartman: No. It doesn’t feel like a Brexit moment, because the vote on the reasonableness clause is not big enough. The election itself was more significant. The proposal of the reform was more significant. The “reasonableness” clause was the perfect issue for Netanyahu to pick, because it’s the most reasonable of the judicial reform proposals. Overall there are five big reform proposals, including the way the Israeli Supreme Court is selected, the power of the attorneys general and the “override” clause. The last is the one the haredi Orthodox want because no matter who is on the Supreme Court or what they decide they could just cancel it out. That’s just the end of democracy.

So Netanyahu pushed the right one for a first victory, but in order to stop the slippery slope process, [the opposition] had to pretend as if this was very big. It was a tactical game, to claim that the override clause was the end of democracy. Tom Friedman overplayed his cards. Nope. It’s far from the end.

This was just the beginning of a three-year war. This is going to go on until the next elections in 2026.

Carol: You said the 2022 election was the real watershed moment. In what way?

Hartman: The consequence of the election was the judicial reform proposals, which raised a fundamental question: What is the nature of our country? Trump wasn’t the end of America, but his election asked the question, What is America?

Carol: Can Israelis right the ship as they see it in the next election?

Hartman: I believe this is the last Likud-led government and it certainly is the last right-wing government. That’s assuming that Netanyahu is not going to be prime minister. This whole reform issue has created an awareness that there are different coalitions being formed in Israel, which aren’t being formed around the right-left wing divide. That divide doesn’t really exist anymore. There is a broad centrist camp that agrees on Judea and Samaria [the West Bank] and economic theory. And there is no possibility of a two-state solution anyway — I just don’t know how to implement it. On the fringes, there is a left-wing socialist camp, let’s call it, and there is a right-wing settler group. Other than that, 80% of Israel is not divided under the left wing-right wing categories. You see at the demonstrations and in the polls that 20 to 30% of those who used to be on the right or are still on the right no longer want to vote for Netanyahu, Smotrich and Ben-Gvir. They want to find alternative expressions for their identities.

What we need to do over the next three years is to frame a new social coalition in Israel, around internal values of liberal Zionism and liberal Judaism, which 80% of Israelis accept. Then we can win and that’s where 2026 is going to change.

Carol: You used the term “liberal Zionist” before. I think you use it differently than an American Jew might. Here it means someone who is pro-Israel but is desperate to see a resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Hartman: It’s very interesting how the category of liberalism has been reclaimed in Israeli society. While in America the term is very divisive, actually in Israel it is becoming much more inclusive. It’s the old liberalism of liberties — a belief in Zionism and the right of the Jewish people to a state but one that believes in human rights and a diverse public sphere and that respects law and the Supreme Court. It’s the old Likud. It’s the old [Ze’ev] Jabotinsky [the pre-state leader of Revisionist Zionism]. It’s the old [Likud Prime Minister] Menachem Begin. It’s not Smotrich or Ben-Gvir, and it’s not the haredi parties.

Carol: But it doesn’t extend to the Palestinian issue.

Hartman: Liberal Zionism in Israel recognizes that we don’t want to be an occupier of another people. But for the vast majority of Israelis, “the Palestinians want to murder me.” There is no Palestinian Authority today. The Palestinian Authority controls the Mukata [the P.A. headquarters in Ramallah] and three upper-middle-class towns in Judea and Samaria. Hamas and Islamic Jihad would run away with any election. It’s very hard to even have a conversation about Palestinian rights in Israel, when you feel you’re talking about a society that wants to kill you.

I just finished a book that is getting published in November, and I have a whole section on it challenging North American liberal Jews to recognize that they have liberal partners in Israel, even though they don’t agree with you on Judea and Samaria, or the West Bank, or what you even call it.

Carol: Since we’re talking on Tisha B’Av, I went to services last night and the person who led the services gave a scorched-earth lament for Israel, basically saying his dreams for Israel are dying and he tied the week’s events, as a lot of people have, to the cataclysms that we acknowledge on the fast day, including the destruction of the First and Second Temples. What are you telling either Israelis or Diaspora supporters of Israel who are talking in apocalyptic terms about this week’s vote and the push for judicial reform by this government?

Hartman: We mourn the destruction of the Temple. We learn from the destruction of the Temple. But we don’t declare the Temple destroyed before it’s destroyed.

Everything in Jewish history is about hope. It’s about working under impossible conditions. And Israel is now working under impossible conditions. That’s true. There is a government which is advocating for an Israel that half of Israel and 90% of North American Jewry wants nothing to do with. But Israel is not defined by its government alone, as you discovered when it came to Trump. People have a voice. What the demonstrations make clear is that the vast majority of Israelis do not support these proposals.

It’s one thing to turn your back on the Israeli government. But we’re out there marching. We don’t embrace destruction before it happens, but we get to work. There is a blueprint forward. The vast majority of Israelis now are embracing a liberal Zionism of the type I mentioned. North American Jews now have partners. They might not be perfect partners, but they have partners. Why walk away from Israel, when the majority of Israelis are now saying things they never said before: “I care about the Supreme Court. I care about human rights. I care about the rights of minorities”? This is what they’re talking about at every demonstration.

So I would go back to your [prayer leader] and say to him, “We waited 2,000 freaking years to have this country. Could you wait three more years? And could you fight for three years?” Because if you fight and you stand up and you don’t walk away, there are partners in Israel who are looking at you and who feel encouraged by you. We can build it. (Excerpted from an article by ANDREW SILOW-CARROLL in the Jewish Telegraphic Agency)

Rabbi Donniel Hartman is urging critics of the judicial reforms and Netanyahu’s government to take a deep breath. Not because he supports the proposals — he agrees they would “undermine the systems of checks and balances necessary to protect Israel’s democratic identity.” But he warns that the bill passed on Monday represents one of the least controversial planks in Netanyahu’s reform plan, and that the massive demonstrations against the proposals have united an Israeli consensus around what he is calling a “new social coalition.”

An interview with Rabbi Donniel Hartman:

Carol: I’ve been thinking of the “day after” fear and anticipation after some recent watershed events – Trump’s election, the Dobbs decision that overturned Roe v. Wade, maybe the Brexit vote. Did Monday’s vote on the “reasonableness” clause mark a before and after?

Hartman: No. It doesn’t feel like a Brexit moment, because the vote on the reasonableness clause is not big enough. The election itself was more significant. The proposal of the reform was more significant. The “reasonableness” clause was the perfect issue for Netanyahu to pick, because it’s the most reasonable of the judicial reform proposals. Overall there are five big reform proposals, including the way the Israeli Supreme Court is selected, the power of the attorneys general and the “override” clause. The last is the one the haredi Orthodox want because no matter who is on the Supreme Court or what they decide they could just cancel it out. That’s just the end of democracy.

So Netanyahu pushed the right one for a first victory, but in order to stop the slippery slope process, [the opposition] had to pretend as if this was very big. It was a tactical game, to claim that the override clause was the end of democracy. Tom Friedman overplayed his cards. Nope. It’s far from the end.

This was just the beginning of a three-year war. This is going to go on until the next elections in 2026.

Carol: You said the 2022 election was the real watershed moment. In what way?

Hartman: The consequence of the election was the judicial reform proposals, which raised a fundamental question: What is the nature of our country? Trump wasn’t the end of America, but his election asked the question, What is America?

Carol: Can Israelis right the ship as they see it in the next election?

Hartman: I believe this is the last Likud-led government and it certainly is the last right-wing government. That’s assuming that Netanyahu is not going to be prime minister. This whole reform issue has created an awareness that there are different coalitions being formed in Israel, which aren’t being formed around the right-left wing divide. That divide doesn’t really exist anymore. There is a broad centrist camp that agrees on Judea and Samaria [the West Bank] and economic theory. And there is no possibility of a two-state solution anyway — I just don’t know how to implement it. On the fringes, there is a left-wing socialist camp, let’s call it, and there is a right-wing settler group. Other than that, 80% of Israel is not divided under the left wing-right wing categories. You see at the demonstrations and in the polls that 20 to 30% of those who used to be on the right or are still on the right no longer want to vote for Netanyahu, Smotrich and Ben-Gvir. They want to find alternative expressions for their identities.

What we need to do over the next three years is to frame a new social coalition in Israel, around internal values of liberal Zionism and liberal Judaism, which 80% of Israelis accept. Then we can win and that’s where 2026 is going to change.

Carol: You used the term “liberal Zionist” before. I think you use it differently than an American Jew might. Here it means someone who is pro-Israel but is desperate to see a resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Hartman: It’s very interesting how the category of liberalism has been reclaimed in Israeli society. While in America the term is very divisive, actually in Israel it is becoming much more inclusive. It’s the old liberalism of liberties — a belief in Zionism and the right of the Jewish people to a state but one that believes in human rights and a diverse public sphere and that respects law and the Supreme Court. It’s the old Likud. It’s the old [Ze’ev] Jabotinsky [the pre-state leader of Revisionist Zionism]. It’s the old [Likud Prime Minister] Menachem Begin. It’s not Smotrich or Ben-Gvir, and it’s not the haredi parties.

Carol: But it doesn’t extend to the Palestinian issue.

Hartman: Liberal Zionism in Israel recognizes that we don’t want to be an occupier of another people. But for the vast majority of Israelis, “the Palestinians want to murder me.” There is no Palestinian Authority today. The Palestinian Authority controls the Mukata [the P.A. headquarters in Ramallah] and three upper-middle-class towns in Judea and Samaria. Hamas and Islamic Jihad would run away with any election. It’s very hard to even have a conversation about Palestinian rights in Israel, when you feel you’re talking about a society that wants to kill you.

I just finished a book that is getting published in November, and I have a whole section on it challenging North American liberal Jews to recognize that they have liberal partners in Israel, even though they don’t agree with you on Judea and Samaria, or the West Bank, or what you even call it.

Carol: Since we’re talking on Tisha B’Av, I went to services last night and the person who led the services gave a scorched-earth lament for Israel, basically saying his dreams for Israel are dying and he tied the week’s events, as a lot of people have, to the cataclysms that we acknowledge on the fast day, including the destruction of the First and Second Temples. What are you telling either Israelis or Diaspora supporters of Israel who are talking in apocalyptic terms about this week’s vote and the push for judicial reform by this government?

Hartman: We mourn the destruction of the Temple. We learn from the destruction of the Temple. But we don’t declare the Temple destroyed before it’s destroyed.

Everything in Jewish history is about hope. It’s about working under impossible conditions. And Israel is now working under impossible conditions. That’s true. There is a government which is advocating for an Israel that half of Israel and 90% of North American Jewry wants nothing to do with. But Israel is not defined by its government alone, as you discovered when it came to Trump. People have a voice. What the demonstrations make clear is that the vast majority of Israelis do not support these proposals.

It’s one thing to turn your back on the Israeli government. But we’re out there marching. We don’t embrace destruction before it happens, but we get to work. There is a blueprint forward. The vast majority of Israelis now are embracing a liberal Zionism of the type I mentioned. North American Jews now have partners. They might not be perfect partners, but they have partners. Why walk away from Israel, when the majority of Israelis are now saying things they never said before: “I care about the Supreme Court. I care about human rights. I care about the rights of minorities”? This is what they’re talking about at every demonstration.

So I would go back to your [prayer leader] and say to him, “We waited 2,000 freaking years to have this country. Could you wait three more years? And could you fight for three years?” Because if you fight and you stand up and you don’t walk away, there are partners in Israel who are looking at you and who feel encouraged by you. We can build it. (Excerpted from an article by ANDREW SILOW-CARROLL in the Jewish Telegraphic Agency)

Why do we fast on Tisha B'Av?

Tisha B’Av, the ninth of the month of Av, is a day of mourning for Jews. It is the day Jews remember the destruction of both Temples that once stood in Jerusalem as well as a number of other tragedies that have befallen the Jewish people over the course of history.

Nine days prior to Tisha B’Av, a new period of more intense mourning begins. Traditional Jews do not eat meat, cut their hair, or wash their clothes unless they are to be worn again during the nine days. All these actions are considered signs of joy or luxury inappropriate for this time of mourning.

Tisha B’Av is a full fast day, so the last meal must be eaten before sunset prior to the ninth of Av. The meal often is comprised of round foods like eggs or lentils, which symbolize mourning in Jewish tradition because they evoke the cycle of life.

Megillat Eicha (the Scroll of Lamentations), which is a lament for the destruction of the First Temple, is chanted during the Maariv service, along with several kinot, elegies or dirges written at different periods of Jewish history. The kinot speak of the suffering and pain of Jewish tragedy through the ages. An extended set of kinot are traditionally recited during the morning service, and some communities repeat the chanting of Eicha in the morning as well.

The meal ending the fast traditionally omits meat and wine, in acknowledgment of the fact that the burning of the Temple continued until the next day. Finally, the sorrow that began on the 17th of Tammuz comes to a halt and the Shabbat immediately following Tishah B’Av is called Shabbat Nahamu (Shabbat of comfort) because the Haftarah begins with the words “nahamu nahamu ami” (“comfort, comfort my people”). This begins a period of consolation and comfort leading up to Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. (Sourced in part from myJewishlearning.com)

Nine days prior to Tisha B’Av, a new period of more intense mourning begins. Traditional Jews do not eat meat, cut their hair, or wash their clothes unless they are to be worn again during the nine days. All these actions are considered signs of joy or luxury inappropriate for this time of mourning.

Tisha B’Av is a full fast day, so the last meal must be eaten before sunset prior to the ninth of Av. The meal often is comprised of round foods like eggs or lentils, which symbolize mourning in Jewish tradition because they evoke the cycle of life.

Megillat Eicha (the Scroll of Lamentations), which is a lament for the destruction of the First Temple, is chanted during the Maariv service, along with several kinot, elegies or dirges written at different periods of Jewish history. The kinot speak of the suffering and pain of Jewish tragedy through the ages. An extended set of kinot are traditionally recited during the morning service, and some communities repeat the chanting of Eicha in the morning as well.

The meal ending the fast traditionally omits meat and wine, in acknowledgment of the fact that the burning of the Temple continued until the next day. Finally, the sorrow that began on the 17th of Tammuz comes to a halt and the Shabbat immediately following Tishah B’Av is called Shabbat Nahamu (Shabbat of comfort) because the Haftarah begins with the words “nahamu nahamu ami” (“comfort, comfort my people”). This begins a period of consolation and comfort leading up to Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. (Sourced in part from myJewishlearning.com)

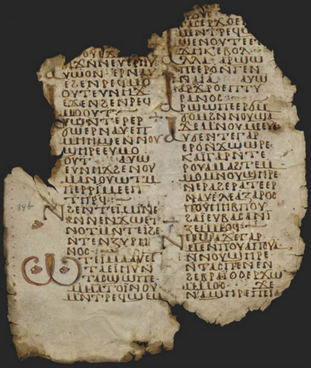

What is the Book of Lamantations (Megilat Eicha)?

Lamentations is one of the Five “Scrolls” (megillot) in the Hebrew Bible (The others are Esther, Song of Songs, Ruth, and Kohelet, also known as Ecclesiastes). The text begins with the Hebrew word Eicha (how?), and the book is known in Hebrew as Megillat Eicha (the scroll of Eicha.) The book is a theological and prophetic response to the destruction of the First Temple (Beit Hamikdash), in Jerusalem, in 586 B.C.E. The Talmud (The Babylonian, Tractate Bava Batra 15a) states that it was written by the prophet Jeremiah, who lived at the time of the destruction.

In 586 B.C.E., the army of the Babylonian empire destroyed Jerusalem and its Temple because the kingdom of Judah, of which Jerusalem was the capital, refused to remain a loyal vassal of Babylonia. The king of Babylonia at the time, Nebuchadnezzar, sought to counter Egyptian military power and political influence in Syria-Palestine, and so control of Judah was particularly important to him. Jerusalem was destroyed, and large parts of the population were exiled to Babylon.

But Lamentations is not concerned with the technical historical details of the destruction, but rather with larger and meta-historical issues: Why did God, who had once been Israel’s redeemer, acquiesce to the destruction of His holy city and temple? Why is God’s love no longer evident? How can it be that “the city that was full of people” now “dwells alone” (Lamentations 1:1)?

Lamentations offers more questions than answers, but asking these questions is an important step in dealing with the theological crisis posed by the destruction of the Temple. The book does not question God’s justice in destroying Jerusalem. “Jerusalem has sinned,” the book proclaims in 1:8, and has therefore been punished. Lamentations describes God as participating in the destruction of Jerusalem: “The yoke of my (i.e. Jerusalem’s) sins in his hand is ready. They twine together, come upon my neck, cause my strength to fail. God has given me into the hands of one against whom I cannot stand up” (1:14). Because of Jerusalem’s sins, God has given Jerusalem over to the Babylonians. (Sourced in part from myJewishlearning.com)

In 586 B.C.E., the army of the Babylonian empire destroyed Jerusalem and its Temple because the kingdom of Judah, of which Jerusalem was the capital, refused to remain a loyal vassal of Babylonia. The king of Babylonia at the time, Nebuchadnezzar, sought to counter Egyptian military power and political influence in Syria-Palestine, and so control of Judah was particularly important to him. Jerusalem was destroyed, and large parts of the population were exiled to Babylon.

But Lamentations is not concerned with the technical historical details of the destruction, but rather with larger and meta-historical issues: Why did God, who had once been Israel’s redeemer, acquiesce to the destruction of His holy city and temple? Why is God’s love no longer evident? How can it be that “the city that was full of people” now “dwells alone” (Lamentations 1:1)?

Lamentations offers more questions than answers, but asking these questions is an important step in dealing with the theological crisis posed by the destruction of the Temple. The book does not question God’s justice in destroying Jerusalem. “Jerusalem has sinned,” the book proclaims in 1:8, and has therefore been punished. Lamentations describes God as participating in the destruction of Jerusalem: “The yoke of my (i.e. Jerusalem’s) sins in his hand is ready. They twine together, come upon my neck, cause my strength to fail. God has given me into the hands of one against whom I cannot stand up” (1:14). Because of Jerusalem’s sins, God has given Jerusalem over to the Babylonians. (Sourced in part from myJewishlearning.com)

What Is Yom Yerushalayim, Jerusalem Day?

Yom Yerushalayim — Jerusalem Day — is the most recent addition to the Hebrew calendar. It commemorates the reunification of Jerusalem under Jewish sovereignty in 1967. It is celebrated on the 28th day of Iyar.

Jerusalem became the capital city of the Jewish people in the time of King David who conquered it and made it the seat of his monarchy in approximately 1000 B.C.E. It was conquered twice in antiquity, the second time by the Romans in 70 C.E. The destruction of Jerusalem was a watershed event in Jewish history that began thousands of years of mourning for Jerusalem—including an official day of mourning every year on Tisha B’Av. During the ensuing two millennia of exile, Jerusalem remained the Jews’ spiritual capital. To this day, Jews face in the direction of Jerusalem for prayer and Jewish services are filled with references to Jerusalem. However, there has never been a special day in honor of the city until recent times.

Following the Israeli War of Independence in 1948, the city of Jerusalem was divided, with the older eastern side falling under Jordanian control, and the more recently-developed western side falling under Israeli control. On the third day of the Six-Day War in June 1967, the Israeli army captured the ancient, eastern part of the city. The 1967 victory marked the first time in thousands of years that all of Jerusalem came under Jewish control. It also allowed Jews access to the holiest parts of the city, especially the Western Wall.

Due to the young age of this holiday, there is still not much that makes it unique in terms of customs and traditions. It is gradually becoming a “pilgrimage” day, when thousands of Israelis travel (some hike) to Jerusalem to demonstrate solidarity with the city. This show of solidarity is of special importance to the state of Israel, since the international community has never approved the “reunification” of the city under Israeli sovereignty, and many countries have not recognized Jerusalem as the capital of the Jewish state. (The United Nations “partition plan” of November 1947 assigned a status of “International City” to Jerusalem.)

Following the model of Yom Ha’atzmaut, the Chief Rabbinate of Israel decided that this day should also be marked with the recitation of Hallel. The ambiguity of the religious status of this holiday is reflected in celebrations — or lack thereof — outside of Israel. While the city of Jerusalem has significant meaning for all Jews, Yom Yerushalayim has yet to attain the popularity of Yom Ha’atzmaut and is not observed extensively outside of Israel. (Sourced in part from myJewishlearning.com)

Jerusalem became the capital city of the Jewish people in the time of King David who conquered it and made it the seat of his monarchy in approximately 1000 B.C.E. It was conquered twice in antiquity, the second time by the Romans in 70 C.E. The destruction of Jerusalem was a watershed event in Jewish history that began thousands of years of mourning for Jerusalem—including an official day of mourning every year on Tisha B’Av. During the ensuing two millennia of exile, Jerusalem remained the Jews’ spiritual capital. To this day, Jews face in the direction of Jerusalem for prayer and Jewish services are filled with references to Jerusalem. However, there has never been a special day in honor of the city until recent times.

Following the Israeli War of Independence in 1948, the city of Jerusalem was divided, with the older eastern side falling under Jordanian control, and the more recently-developed western side falling under Israeli control. On the third day of the Six-Day War in June 1967, the Israeli army captured the ancient, eastern part of the city. The 1967 victory marked the first time in thousands of years that all of Jerusalem came under Jewish control. It also allowed Jews access to the holiest parts of the city, especially the Western Wall.

Due to the young age of this holiday, there is still not much that makes it unique in terms of customs and traditions. It is gradually becoming a “pilgrimage” day, when thousands of Israelis travel (some hike) to Jerusalem to demonstrate solidarity with the city. This show of solidarity is of special importance to the state of Israel, since the international community has never approved the “reunification” of the city under Israeli sovereignty, and many countries have not recognized Jerusalem as the capital of the Jewish state. (The United Nations “partition plan” of November 1947 assigned a status of “International City” to Jerusalem.)

Following the model of Yom Ha’atzmaut, the Chief Rabbinate of Israel decided that this day should also be marked with the recitation of Hallel. The ambiguity of the religious status of this holiday is reflected in celebrations — or lack thereof — outside of Israel. While the city of Jerusalem has significant meaning for all Jews, Yom Yerushalayim has yet to attain the popularity of Yom Ha’atzmaut and is not observed extensively outside of Israel. (Sourced in part from myJewishlearning.com)

Judicial Reform In Israel, What's the fuss all about?

At the inaugural Younes Nazarian Memorial Lecture of the UCLA Y&S Nazarian Center for Israel Studies, writer Yossi Klein Halevi contended that mass demonstrations against the proposed judicial reforms of Prime Minister Netanyahu were reanimating the center in Israeli politics.

By Peggy McInerny, Director of Communications

“To be a liberal Israeli these days is to experience an anguish that I’ve never known in the 40 years that I’ve lived in Israel,” said Yossi Klein Halevi, who immigrated to the country from the U.S. in 1982. “I never recall losing sleep the way that I do now.

“What we’re experiencing in Israel is a convergence of assaults. This is the most corrupt, most politically extreme and most religiously fundamentalist government in Israel’s history. Any one of those assaults would be a formidable challenge. Coming together, [they have] really brought us to the edge of what feels like the abyss.”

A conflict over the meaning of Israel’s dual identities

Israel today is living through a dispute between the center and the right over what a Jewish state and a democratic state mean, said Halevi. Proposed reforms that would reduce the independence of the Israeli Supreme Court have sparked huge demonstrations nationwide by Israeli citizens, many of whom also object to the inclusion of extreme far-right politicians in the cabinet of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

“The debate that we’re having today over democracy is: How do you define majority rule? Does a majority have the right to do whatever it decides if [it] wins an election, as this government did? Does winner take all? This government is saying, yes, we won the election and to oppose us is to oppose the democratic process.

“The liberal understanding of democracy is that there’s a delicate dance between the rights of the majority and the rights of a minority. When the government says that the [Supreme] Court is an undemocratic institution, they’re right. That’s its purpose. Its purpose is to be a check on [the] runaway power of an elected majority. And so there’s a profound disagreement [over] what we mean by democracy.”

Israel is not and never well be a paragon of pure democracy because it must constantly mediate between democratic norms and serious security threats, observed Halevi. “What makes Israeli democracy so precious, and I would argue so important for the world, is [that we are] the test case of democracy under extremity.

“I fear this government would up-end precisely that delicate balance, that search for decency under conditions that I believe would have defeated almost any country in our place.

“The second identity issue that is on the table,” he continued, “and I believe [will] become more and more prominent in the coming months, is what do we mean by a Jewish state?

“The classical Zionist, mainstream answer to this question, going back to the founding of Zionism, [is] that Israel was meant to be the state of the Jewish people, all of the Jewish people.”

In Halevi’s view, Rabbinic Judaism succeeded in holding the Jews together for 1,700 years in the diaspora, but broke down in the face of modernity in the 19th century, when Zionism arose to offer an alternative version of a unifying Jewish identity.

“There is good reason for why almost the entire ultra-Orthodox world in… pre-Holocaust Europe opposed Zionism, because they understood just how radical, how revolutionary Zionism was,” he continued.

“Now, it’s true that Zionism and the secular state went a long way to accommodat[e] the camp that defines ‘who is a Jew’ in classical Rabbinic Orthodox terms,” he commented. “I would define Israel as a secular state with too many religious laws… maybe like Ireland or Italy of two generations ago.

“The one [law] that most defines Israel as the state of the Jewish people, and not the state of Orthodox Judaism, is the Law of Return. And that’s precisely what this government intends to amend. So the next great fight that’s heading our way is going to be over how we define admission into the state of Israel.”

The contending definitions of Israel as a Jewish state highlight the difference between a modern state and a people, observed Halevi, who argued that the ultra-Orthodox and religious Zionists confuse a community with a people, and do not have an expansive notion of a modern state.

“For me, the definition of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state is that… Israel is, first of all, the state of every Jew in the world, whether or not they are citizens of Israel. And secondly, it is the state of all of its citizens, whether or not they are Jews.

“This government wants to expand and expand and expand the Jewishness of the state. And that seems to be antithetical to Israel’s best long term interests, which require the absorption to whatever extent is possible of Arab citizens into some sense of shared civic Israeli identity.”

Despite the gravity of the current political situation, Halevi was ultimately optimistic. “This is potentially one of the most positive moments in Israeli history,” he said.

“And I say that because it has forced us not only to deal with identity issues that we must confront, but also to deal with the long-simmering distortions in the Israeli system.” Among those distortions, he identified both “the ultra-Orthodox state within a state” and settler violence, which he believes has moved from the farthest fringe of the Israeli right to the heart of Israeli power.

“What we’re experiencing today on the streets is the rise of a passionate center,” he concluded. “The center in Israel today is no less passionate, no less militant, than the extremes.

“[T]he center has …moved from a mood to an ideology. And that ideology is what I’ve tried to lay out here: a liberal understanding, a classical Zionist understanding of Israel as a Jewish state and a democratic state, and [an insistence] on the non-negotiable entwinement of these two identities.

“On the left, there is a wavering about a Jewish state. On the right, we’re seeing the erosion of support for a democratic state. It’s the center that will fight and preserve, I believe, the integrity of these two identities.”

Watch the video of Halevi's full presentation here.

From the Hartman Institute website

By Peggy McInerny, Director of Communications

“To be a liberal Israeli these days is to experience an anguish that I’ve never known in the 40 years that I’ve lived in Israel,” said Yossi Klein Halevi, who immigrated to the country from the U.S. in 1982. “I never recall losing sleep the way that I do now.

“What we’re experiencing in Israel is a convergence of assaults. This is the most corrupt, most politically extreme and most religiously fundamentalist government in Israel’s history. Any one of those assaults would be a formidable challenge. Coming together, [they have] really brought us to the edge of what feels like the abyss.”

A conflict over the meaning of Israel’s dual identities

Israel today is living through a dispute between the center and the right over what a Jewish state and a democratic state mean, said Halevi. Proposed reforms that would reduce the independence of the Israeli Supreme Court have sparked huge demonstrations nationwide by Israeli citizens, many of whom also object to the inclusion of extreme far-right politicians in the cabinet of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

“The debate that we’re having today over democracy is: How do you define majority rule? Does a majority have the right to do whatever it decides if [it] wins an election, as this government did? Does winner take all? This government is saying, yes, we won the election and to oppose us is to oppose the democratic process.

“The liberal understanding of democracy is that there’s a delicate dance between the rights of the majority and the rights of a minority. When the government says that the [Supreme] Court is an undemocratic institution, they’re right. That’s its purpose. Its purpose is to be a check on [the] runaway power of an elected majority. And so there’s a profound disagreement [over] what we mean by democracy.”

Israel is not and never well be a paragon of pure democracy because it must constantly mediate between democratic norms and serious security threats, observed Halevi. “What makes Israeli democracy so precious, and I would argue so important for the world, is [that we are] the test case of democracy under extremity.

“I fear this government would up-end precisely that delicate balance, that search for decency under conditions that I believe would have defeated almost any country in our place.

“The second identity issue that is on the table,” he continued, “and I believe [will] become more and more prominent in the coming months, is what do we mean by a Jewish state?

“The classical Zionist, mainstream answer to this question, going back to the founding of Zionism, [is] that Israel was meant to be the state of the Jewish people, all of the Jewish people.”

In Halevi’s view, Rabbinic Judaism succeeded in holding the Jews together for 1,700 years in the diaspora, but broke down in the face of modernity in the 19th century, when Zionism arose to offer an alternative version of a unifying Jewish identity.

“There is good reason for why almost the entire ultra-Orthodox world in… pre-Holocaust Europe opposed Zionism, because they understood just how radical, how revolutionary Zionism was,” he continued.

“Now, it’s true that Zionism and the secular state went a long way to accommodat[e] the camp that defines ‘who is a Jew’ in classical Rabbinic Orthodox terms,” he commented. “I would define Israel as a secular state with too many religious laws… maybe like Ireland or Italy of two generations ago.

“The one [law] that most defines Israel as the state of the Jewish people, and not the state of Orthodox Judaism, is the Law of Return. And that’s precisely what this government intends to amend. So the next great fight that’s heading our way is going to be over how we define admission into the state of Israel.”

The contending definitions of Israel as a Jewish state highlight the difference between a modern state and a people, observed Halevi, who argued that the ultra-Orthodox and religious Zionists confuse a community with a people, and do not have an expansive notion of a modern state.

“For me, the definition of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state is that… Israel is, first of all, the state of every Jew in the world, whether or not they are citizens of Israel. And secondly, it is the state of all of its citizens, whether or not they are Jews.

“This government wants to expand and expand and expand the Jewishness of the state. And that seems to be antithetical to Israel’s best long term interests, which require the absorption to whatever extent is possible of Arab citizens into some sense of shared civic Israeli identity.”

Despite the gravity of the current political situation, Halevi was ultimately optimistic. “This is potentially one of the most positive moments in Israeli history,” he said.

“And I say that because it has forced us not only to deal with identity issues that we must confront, but also to deal with the long-simmering distortions in the Israeli system.” Among those distortions, he identified both “the ultra-Orthodox state within a state” and settler violence, which he believes has moved from the farthest fringe of the Israeli right to the heart of Israeli power.

“What we’re experiencing today on the streets is the rise of a passionate center,” he concluded. “The center in Israel today is no less passionate, no less militant, than the extremes.

“[T]he center has …moved from a mood to an ideology. And that ideology is what I’ve tried to lay out here: a liberal understanding, a classical Zionist understanding of Israel as a Jewish state and a democratic state, and [an insistence] on the non-negotiable entwinement of these two identities.

“On the left, there is a wavering about a Jewish state. On the right, we’re seeing the erosion of support for a democratic state. It’s the center that will fight and preserve, I believe, the integrity of these two identities.”

Watch the video of Halevi's full presentation here.

From the Hartman Institute website

Why do we read the Book Of Ruth on Shavuot?

In traditional settings, the Book Of Ruth is read on the second day of Shavuot. The book is about a Moabite woman who, after her husband dies, follows her Israelite mother-in-law, Naomi, into the Jewish people with the famous words “whither you go, I will go, wherever you lodge, I will lodge, your people will be my people, and your God will be my God.” She asserts the right of the poor to glean the leftovers of the barley harvest, breaks the normal rules of behavior to confront her kinsman Boaz, is redeemed by him for marriage, and becomes the ancestor of King David.

The custom of reading the Book Of Ruth is already mentioned in the Talmudic tractate of Soferim (14:16), and the fact that the first chapter of the Midrash of Ruth deals with the giving of the Torah is evidence that this custom was already well established by the time this Midrash was compiled.

There are many explanations given for the reading of Ruth on Shavuot. The most quoted reason is that Ruth’s coming to Israel took place around the time of Shavuot, late spring, and her acceptance into the Jewish faith was analogous to the Jewish people accepting God’s Torah.

A second explanation relates to genealogy. Since the Book Of Ruth ends with the genealogy of David, Ruth being his forbearer, it has been suggested that it is read on Shavuot because King David is believed to have died on Shavuot.

Another reason for the reading of Ruth on Shavuot is that its story takes place at harvest time, Ruth meeting Boaz out in the fields during harvest. The holiday of Shavuot also occurs at the time of the spring harvest.

The story of Ruth’s conversion to Judaism teaches us humility and gratitude about our Jewish identity. It suggests that our Jewishness is not guaranteed but rather requires that we continually reconvert, like Ruth, and accept the Torah of our ancestors each year anew.

By RABBI RONALD H. ISAACS (Sourced in part from myJewishlearning.com)

The custom of reading the Book Of Ruth is already mentioned in the Talmudic tractate of Soferim (14:16), and the fact that the first chapter of the Midrash of Ruth deals with the giving of the Torah is evidence that this custom was already well established by the time this Midrash was compiled.

There are many explanations given for the reading of Ruth on Shavuot. The most quoted reason is that Ruth’s coming to Israel took place around the time of Shavuot, late spring, and her acceptance into the Jewish faith was analogous to the Jewish people accepting God’s Torah.

A second explanation relates to genealogy. Since the Book Of Ruth ends with the genealogy of David, Ruth being his forbearer, it has been suggested that it is read on Shavuot because King David is believed to have died on Shavuot.

Another reason for the reading of Ruth on Shavuot is that its story takes place at harvest time, Ruth meeting Boaz out in the fields during harvest. The holiday of Shavuot also occurs at the time of the spring harvest.

The story of Ruth’s conversion to Judaism teaches us humility and gratitude about our Jewish identity. It suggests that our Jewishness is not guaranteed but rather requires that we continually reconvert, like Ruth, and accept the Torah of our ancestors each year anew.

By RABBI RONALD H. ISAACS (Sourced in part from myJewishlearning.com)

Why study Torah all night on the holiday of Shavuot?

The holiday of Shavuot, celebrated this coming week, is understood by Jewish tradition to be the time when God gave the Israelites the Torah at Mount Sinai. It is traditionally celebrated with dairy foods and intensive Torah study, with some staying up all night to learn. These all-night study sessions, known as Tikkun Leil Shavuot, are held by Jewish communities of different denominations and geographies and are the only widely observed Jewish ritual involving staying up all night. Though the custom is widespread, there are few classical sources to support it. So why do we do it?

On its face, the connection is obvious. Shavuot celebrates receiving the Torah, so of course we would honor Shavuot with abundant Torah study. But upon reflection, this reason seems less than convincing. How high is the quality of Torah study in the middle of the night? As the hours tick by, is anyone even paying attention to the teacher?

A more common explanation is that Tikkun Leil Shavuot is precisely that — a tikkun (literally “rectification”) for what went wrong on that original Shavuot at Sinai. The Israelites, according to this commentary, slept-in on the day they were meant to receive the Torah. In a sort of penance for that failing, we make sure not to miss Shavuot morning by pulling an all-nighter the night before.

I would like to suggest an alternate explanation, one focused less on learning and preparedness and more on the experience of receiving the Torah. The goal of Shavuot night is not Torah learning — one can study Torah any day of the year. The goal is to experience something of the radical encounter with God at Sinai.

In the book of Exodus, we find this description of what had transpired as God descended on the mountain: “And the entire people saw the thunder and lightning and the sound of the shofar and the mountain in smoke. The nation saw, they trembled with fear, and they stayed at a distance. They said to Moses, ‘Speak to us yourself and we will listen. But do not have God speak to us or we will die.’”

In the Torah’s telling, the encounter with God was an immersive experience. As if attending a concert with overwhelming audiovisual components, the people are at first entranced and then overwhelmed by what they’re experiencing, backtracking in fear. They are so overpowered they are unable to distinguish between the senses — hence they “saw” the “sound of the shofar.” Overawed by all of this, they beg off, asking to have Moses serve as an intermediary rather than encounter God directly again.

This should not be surprising — it makes sense that an encounter with God should be overwhelming, an experience that scrambles the senses and shifts one’s consciousness. And that’s what we’re looking for on Shavuot. Tikkun Leil Shavuot isn’t primarily an opportunity to learn, nor a chance to fix some millennia-old mishap. It is meant precisely to simulate that total immersive experience.

We do that by occupying ourselves entirely with Torah — and nothing else. We learn until exhausted, going at it until we just can’t anymore. Depriving ourselves of sleep brings our body into the experience inevitably effecting a shift in consciousness. Taken together, this practice creates an intense experience, an all-encompassing engagement with God and Torah — just as the Israelites experienced at Mount Sinai.

BY RABBI SHLOMO ZUCKIER. This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Shabbat newsletter Recharge on May 20, 2023. To sign up to receive Recharge each week in your inbox, click here.

On its face, the connection is obvious. Shavuot celebrates receiving the Torah, so of course we would honor Shavuot with abundant Torah study. But upon reflection, this reason seems less than convincing. How high is the quality of Torah study in the middle of the night? As the hours tick by, is anyone even paying attention to the teacher?

A more common explanation is that Tikkun Leil Shavuot is precisely that — a tikkun (literally “rectification”) for what went wrong on that original Shavuot at Sinai. The Israelites, according to this commentary, slept-in on the day they were meant to receive the Torah. In a sort of penance for that failing, we make sure not to miss Shavuot morning by pulling an all-nighter the night before.

I would like to suggest an alternate explanation, one focused less on learning and preparedness and more on the experience of receiving the Torah. The goal of Shavuot night is not Torah learning — one can study Torah any day of the year. The goal is to experience something of the radical encounter with God at Sinai.

In the book of Exodus, we find this description of what had transpired as God descended on the mountain: “And the entire people saw the thunder and lightning and the sound of the shofar and the mountain in smoke. The nation saw, they trembled with fear, and they stayed at a distance. They said to Moses, ‘Speak to us yourself and we will listen. But do not have God speak to us or we will die.’”

In the Torah’s telling, the encounter with God was an immersive experience. As if attending a concert with overwhelming audiovisual components, the people are at first entranced and then overwhelmed by what they’re experiencing, backtracking in fear. They are so overpowered they are unable to distinguish between the senses — hence they “saw” the “sound of the shofar.” Overawed by all of this, they beg off, asking to have Moses serve as an intermediary rather than encounter God directly again.

This should not be surprising — it makes sense that an encounter with God should be overwhelming, an experience that scrambles the senses and shifts one’s consciousness. And that’s what we’re looking for on Shavuot. Tikkun Leil Shavuot isn’t primarily an opportunity to learn, nor a chance to fix some millennia-old mishap. It is meant precisely to simulate that total immersive experience.

We do that by occupying ourselves entirely with Torah — and nothing else. We learn until exhausted, going at it until we just can’t anymore. Depriving ourselves of sleep brings our body into the experience inevitably effecting a shift in consciousness. Taken together, this practice creates an intense experience, an all-encompassing engagement with God and Torah — just as the Israelites experienced at Mount Sinai.

BY RABBI SHLOMO ZUCKIER. This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Shabbat newsletter Recharge on May 20, 2023. To sign up to receive Recharge each week in your inbox, click here.

How do we celebrate Yom Haatzma'ut, Israel's Independence Day?

Yom Haatzmaut, Israel’s Independence Day is celebrated on the fifth day of the month of Iyar, which is the Hebrew date of the formal establishment of the State of Israel, when members of the “provisional government” read and signed a Declaration of Independence in Tel Aviv. The original date corresponded to May 14, 1948.

Most of the Jewish communities in the Western world have incorporated this modern holiday into their calendars, but some North American Jewish communities hold the public celebrations on a following Sunday in order to attract more participation. In the State of Israel it is a formal holiday, so almost everyone has the day off.

Yom Ha’atzmaut in Israel is always preceded by Yom Hazikaron, Israel’s Memorial Day for the fallen soldiers. The official “switch” from Yom Hazikaron to Yom Ha’atzmaut takes place a few minutes after sundown, with a ceremony on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem in which the flag is raised from half staff (due to Memorial Day) to the top of the pole.

The president of Israel delivers a speech of congratulations, and soldiers representing the Army, Navy, and Air Force parade with their flags. In recent decades this small-scale parade has replaced the large-scale daytime parade, which was the main event during the 1950s and ’60s. The evening parade is followed by a torch lighting (hadlakat masuot) ceremony, which marks the country’s achievements in all spheres of life.

Israeli citizens celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut in a variety of ways. In the cities, the nighttime festivities may be found on the main streets. Crowds will gather to watch public shows offered for free by the municipalities and the government. Many spend the night dancing Israeli folk-dances or singing Israeli songs. During the daytime thousands of Israeli families go out on hikes and picnics. Army camps are open for civilians to visit and to display the recent technological achievements of the Israeli Defense Forces. Yom Ha’atzmaut is concluded with the ceremony of granting the “Israel Prize” recognizing individual Israelis for their unique contribution to the country’s culture, science, arts, and the humanities.

The religious character of Yom Ha’atzmaut is still in the process of formation, and is still subject to debate. The Chief Rabbinate of the State (which consists of Orthodox rabbis) has decided that this day should be marked with the recitation of Hallel (psalms of praise), similar to other joyous holidays, and with the reading of a special haftarah (prophetic portion). (Sourced in part from myJewishlearning.com)

Most of the Jewish communities in the Western world have incorporated this modern holiday into their calendars, but some North American Jewish communities hold the public celebrations on a following Sunday in order to attract more participation. In the State of Israel it is a formal holiday, so almost everyone has the day off.

Yom Ha’atzmaut in Israel is always preceded by Yom Hazikaron, Israel’s Memorial Day for the fallen soldiers. The official “switch” from Yom Hazikaron to Yom Ha’atzmaut takes place a few minutes after sundown, with a ceremony on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem in which the flag is raised from half staff (due to Memorial Day) to the top of the pole.

The president of Israel delivers a speech of congratulations, and soldiers representing the Army, Navy, and Air Force parade with their flags. In recent decades this small-scale parade has replaced the large-scale daytime parade, which was the main event during the 1950s and ’60s. The evening parade is followed by a torch lighting (hadlakat masuot) ceremony, which marks the country’s achievements in all spheres of life.