The Shahid's Sanctuary - a critique of Zoosman's "The Cost of Revenge... Israel's Response to Hamas"3/30/2024 Dear Cantor Zoosman. Thank you for writing the thoughtful and provocative piece “The Cost of Revenge, A Cantor’s Critique of Israel’s Response to Hamas”. I admire your activism toward the elimination of capital punishment. I have been following your Ohalah posts on the topic from afar. If I wasn’t already overextended I would be active alongside you toward this cause. I absolutely oppose the death penalty. I also appreciate your deep desire for peace between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs as well as your sensitivity to the terrible hardship the war is inflicting on the population in Gaza. I would like to respectfully critique and respond to some of the ideas in your piece.

You wrote the qualifier, “let there be no doubt: the issue of judicial executions and war are markedly distinct.” I appreciate it that you narrowed your analysis to the feelings of revenge that are naturally triggered by extreme criminality as well as by tragic war events, such as the Hamas massacre in Israel on October 7 2023. I also appreciate your suggestions of how revenge feelings can and should be held and handled. Here in Israel we have not yet fully wrapped our minds around the extent of the October 7 tragedy. We have been viciously violated. The internal healing and reckoning will take some time and feelings of revenge are certainly in the mix. A desire for revenge indeed has been expressed in Israel by extremist minority voices in the political arena as well as by folks on the street. An example that comes to mind is my childhood friend, Amnon, who believes in resolving the conflict by exterminating all Gazans. When I confronted him about this extreme view and reminded him of his parents, he did acknowledge that their Nazi concentration camp trauma affects his views. I still remember the sight of his parents’ camp numbers tattooed on their forearms from when we were kids. You do acknowledge the holocaust in your piece and how some survivors found the wherewithal to forgive their Nazi tormentors rather than remain stuck in the prison of their hatred. I have read of several such remarkable cases over the years. Here is where we part ways, though. I disagree with your thesis that the principles behind the objection to the death penalty apply to Israel’s war with Hamas, despite the fact that both engender feelings of revenge. I disagree with your conclusion that the Gaza strip is a “de facto death chamber”. Gaza is rather, if anything, a “suicide chamber”. Granted that media reports from the Gaza war are disheartening and uncomfortable to absorb as the casualties of the ongoing fighting are numerous, yet, while war is incredibly tragic and morbid, this one is by no means comparable to the judicial execution “death chamber”.

7 Comments

My friend and colleague, Rabbi Jan Salzman, said shortly after October 7th 2023 that there are both a Hawk and Dove residing within her head and heart in equal measure. I believe many of us can relate. We are living through a challenging time in which previously set assumptions about life in Israel and about the conflict with our Palestinian cousins are crumbling. The confusion we are experiencing is what crumbling feels like.

There is an aspect of the conflict, especially when attempting to understand the Palestinian motivation for it, that is usually missing from public discourse, that is religion and culture. It has become more evident, especially after October 7th, that understanding the religious aspects of our enemy’s narrative clarifies a number of perplexing questions about the conflict. In the Talmud (Bavli Shabbat) we read that the reason for lighting Hanukkah candles is Pirsumah D’Nisa, פרסומא דניסה, “advertising the miracle” (of Hanukkah). We light the Menorah on a window sill in order to make it visible to the world. The lights are meant as a reminder that the Jewish people suffered oppression by the Greeks, dared to rebel against the superior Greek fighting forces, and with HaShem’s help prevailed.

On this year’s Hanukkah it is hard to ignore that 1200 victims of the massacre have not prevailed but perished instead. Over a hundred hostages are still at risk, which distresses us to no end. The Hebrew word Nes, נס, miracle, shares a root with the word Nisayon, נסיון, testing-experience. For sixty days and counting the horrendous experiences of the Dark Shabbat’s innocent victims along with the heroic experiences of the defenders are being constantly advertised on all media channels, electronic window sills of sorts. The fighting in Gaza to wipeout the Hamas is still raging and broadcast as well. This Hanukkah seems to be up-side-down, tragedy advertised for all to see, and miracles, if any, insufficient to blunt the magnitude of the trauma. When tragedies are being advertised, where is the light? The victims. This year we hold our murdered and captured ones as shining lights, each a bright candle in sharp relief to the shear darkness of their tormentors. We are inspired by the lights of their souls and the stories of their lives, and have vowed to never forget. However, miracles are not all lost. One miracle remains, which is the phenomenon of enduring Jewish hope. We are indeed a stiff-necked nation who have clung onto hope come hell to high water for about 4000 years. Jewish hopefulness can be seen as the constant miracle of miracles. תקווה, hope, shares a root with מקווה, Mikvah, ritual bath. We purify ourselves with the waters of our hope and move on stronger. This is who we, Jews, are and will always be. May the tragic experience of October 7, that has affected us all, turn into greater miracles and more hope for a long time to come. We pray that the one who ordains peace in the heavens ordain peace amongst us, and all of Israel. Wishing you a Hanukkah of light and joy despite all or to spite it all. Happy Hanukkah. Rabbi Reuben modek בתלמוד הבבלי אנו קוראים שהסיבה להדלקת נרות חנוכה הוא פרסומא דניסה, או פרסום הנס. אנו מדליקים את החנוכיה על אדן החלון כדי שכל העולם יראה. אור הנרות משמש כתזכורת שהיהודים דוכאו על ידי היוונים, העיזו למרוד בכוח הצבאי העצום שלהם, ובעזרת השם נצחו. השנה הזאת קשה להתעלם מהעובדה ש1200 קורבנות הטבח הנוראי לא נצחו אלא נרצחו. יותר מ100 בני ערובה עודם בסכנה, מצב הגורם לנו דאגה אין סופית. המילה נס והמילה נסיון הם בעלי אותו השורש. מזה 60 יום הנסיונות המרים של קורבנות השבת השחורה ביחד עם הנסיונות של הלוחמים שבאו לעזרתם מדֻווחים ללא הפסק בערוצי הרשתות למינהם, כמעין אדן חלון אלקטרוני. הלוחמה בעזה לחיסול החמס ממשיך בעוצמה ומשודרת ברשתות גם כן. חנוכה, הבאה עלינו לטובה, נראית כהפוכה על פיה, האסון מפורסם לעיני כל, וכמות הניסים, אם קיימים, קצרי יד מלהקל על גודל הטראומה. כאשר אסונות מפורסמים, היכן האור? הקורבנות הם האור. השנה אנו נושאים את קורבנותינו וחטופינו כאורות זוהרים, כל אחד ואחת נר מאיר בחוזקה כנגד החושך המוחלט של רוצחיהם. אנו שואבים השראה מאור נשמתם וסיפורי חייהם, ונודרים לעולם לא לשכוח. למרות זאת לא נעלמו הניסים מהעולם. נס אחד נשאר על כנו, והוא התקווה היהודית הנצחית. אכן, אנו עם קשה עורף אשר נאחז בתקווה לנוכח כל תלאותינו במשך 4000 השנים האחרונות. אפשר לתאר את התקווה היהודית כנס כל הניסים. תקווה ומקווה הם בעלי אותו השורש. אנחנו מטהרים את עצמינו במימי התקווה וממשיכים הלאה בחזקה. כך אנחנו וכך נהיה לעד. אנו תפילה שהנסיון הנורא של ה7 באוקטובר, שטלטל את כולנו, יהפך לניסים עוד יותר גדולים ותקווה עוד יותר חזקה לעתיד לבוא ולאורך ימים. אנו תפילה שהעושה שלום במרומיו הוא יעשה שלום עלינו ועל כל ישראל. מאחל לך חנוכה של אור וחנוכה של שימחה למרות הכל וכנגד הכל. חג חנוכה שמח, הרב ראובן מודק Friday November 24, 2023 יב כסלו תשפ״ד פרשת ויצא

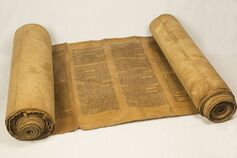

Caring About The Enemy A facebook slogan that has been somewhat viral goes, “I can feel heartbroken for two peoples at the same time”. Among friends and colleagues, especially those of us who are politically progressive, spiritually and emotionally sensitive, and morally conscientious there has been this debate of late: “Is it ok to care about your own people more than you care about your enemy”? Many have said that we can and should care about the other side as much as we do for ours, if not more. Not unlike Jesus’ teaching, when slapped on one cheek turn around and offer the other cheek. Or Gandhi’s approach of nonviolent resistance. Parenthetically, this approach is rooted in the Torah “…love your fellow as yourself, I am BEING” (Leviticus 19:18). I must admit that personally, I am not at an emotional place where I care about the other side equal to my own. Generally speaking, I always care for the other side, as I care for all humanity. I am a humanist, a sensitive soul, and filled with love for all human beings as well as for all animals. But right now it is different for me. Why? Because on a daily basis, here in Israel, we are hearing more and more stories of what had happened to the residents of the south of Israel on the Dark Shabbat of October 7th. 1200 people murdered in one day, many in their bedrooms as they were waking up in the morning. Many burned, many raped, many mutilated. Not pretty. They weren’t bombed from a distance. They weren’t hit by mistake. They weren’t tried in court and executed. They were surprised by young Muslim Arab men heavily armed who came into their neighborhoods and invaded their homes. Many of these Israelis were tortured and slaughtered. Whole families. Sometimes killing children in front of parents or visa versa. Many horrific details were recorded in plain sight by home security cameras. I am not reacting to the number of people murdered, though, but to the number of stories told. For many weeks now, since the Dark Shabbat we are still hearing in the media and off media live interviews with survivors, with relatives of the murdered, and with families of the kidnapped. New stories of the horrors of that day are continually being revealed. The stories occupy much of my consciousness as well as the collective consciousness here in Israel all the time. I turn on the radio in the car, I hear interviews. I watch news at night, I hear interviews. I speak to people as I go about my day, and hear related stories. In addition we continually witness funerals of fallen soldiers and hear stories about their lost lives. A lot to digest. My cousin Avraham and his wife Monika, are from Kibbutz Nir Itzhak by the Gaza strip. Their Kibbutz too was attacked by Hamas terrorists. They hid in their safe room for a whole day, hearing the sounds of shots and shouts in Arabic as the attack progressed. Luckily the terrorists passed over their home and they were eventually evacuated to safety unharmed when the army arrived and killed or pushed back the terrorists. I was in contact with Avraham by WhatsApp as things were happening. I was very relieved when they were finally evacuated. I am not in the mood these days to personally nor authentically care for the Arab Palestinians being killed on the other side, while the Israeli military pursues the murderers and their infrastructure. Call me limited, heartless, un-saintly. Yet this is my emotional and mental truth at this moment. Moreover, I support the military’s invasion of Gaza and its two stated goals: 1. Eliminating the Hamas military and government capabilities. 2. Finding and bringing back the kidnapped hostages. I feel and think that what the military is doing is the right thing right now. I have given much thought to the question of “is it ok to care more about your own relatives than for others, especially your enemy”? At this point I am very clear that for me the answer is yes, it is ok. In my estimation, my colleagues who say they care equally about the Palestinian tragedy are speaking like Saints, but are they? To my ear at this time their talk sounds like moral grandstanding more than anything else. I know a Saint when I see one, and thus far I haven’t heard any in this debate. In my opinion my colleagues are simply hurting like all of us and defaulting to a position of deep denial. Their “Saintly” siding is their way of handling their very justified pain, but in my view, lacking any sound merit. No one should ever be tested, God forbid a million times, but if there would be imminent danger to both my/your child and the child of someone else, and I/you could save only one, which one would I/you save? My child would be my priority, not the other’s. I am not confused about that. Again, we should never be tested ever with such a horrible choice. I am offering this just to illustrate that it is ok, it is natural, to care for your own more than you care for others. Right now, in this situation, I am caring fundamentally for my people, and have very little tolerance for those who in my opinion play “holier than the Pope”. Yet what is the solution to the conflict? The Horrible Shabbat did not happen in a vacuum. It is one more terrible expression of a conflict that has been going on between Arab-Muslims and Jews in Palestine/Israel for about a hundred years. Will it ever end? How does one promote non-violence and peace in this situation? I would love to offer a solution but being in my sixth decade of life I no longer have a simple answer. When I was younger I was idealistic and thought that if we, the Jews, just treated the Palestinian Muslims correctly, with compassion and understanding, and returned the 1967 occupied lands so they can have their own country, there would be peace and all would be ok. I am not convinced about that anymore. It seems to me that we are dealing with an Arab Muslim culture that right now has a powerful evil streak. There are a lot of fanatics amongst them that believe in a violent takeover of the world (not all Muslims do but many, enough to cause terrible mayhem). Hamas is unabashed about its fanatical religious and murderous ideology. Do read their Manifesto carefully, it is available online. That is why they did what they did in the way they did it. Most of their fighters are brainwashed young men who are willing to die for Allah and their cause. Their philosophy is not unlike that of the Natzis, although spiced with Muslim instead of Christian flavor. How do we manage that? I believe that at this point we respond by defending ourselves forcefully. When the Natzis were trying to conquer the world and eliminate the Jews and other undesirables, they would not have stopped if treated only with compassion and generosity. It was the mega military force applied by the allies that saved some Jews from death, albeit not enough. That is why many of us are alive today. Compassionately caring for others is the right thing up to a point. It stops to be right when the other’s stated goal is to kill you, according to Jewish tradition. Then we are obligated to defend ourselves. Right now we, Israeli Jews, need to kill those Arab Muslims who are brainwashed to murder us. They are not only brainwashed to kill Jews but also the rest of the “Infidels" (especially Westerners) in order to create a grand Muslim world Caliphate. According to Torah it is our obligation to preserve our lives. Each his or her life is a gift which we are responsible to treat with care and preservation. It is a spiritual imperative. My prayer and vision is that with God’s help after this terrible war and after sufficiently damaging Hamas, there will be a new space created for peace and the possibility of a new start between Jews and Palestinian Arabs in this area. Not unlike the space created after world war II in Europe. I pray that at that point there will also be a new space within me to care for my Palestinian cousins once again, fully and whole heartedly.  Sermon, Rosh HaShana 2nd Day 5784 Bet Israel Masorti Synagogue, Natanya Israel Rabbi Reuben Modek וַיְהִ֗י אַחַר֙ הַדְּבָרִ֣ים הָאֵ֔לֶּה וְהָ֣אֱלֹהִ֔ים נִסָּ֖ה אֶת־אַבְרָהָ֑ם וַיֹּ֣אמֶר אֵלָ֔יו אַבְרָהָ֖ם וַיֹּ֥אמֶר הִנֵּֽנִי׃ (בראשית כב״ א פרשת וירא) Some time afterward, God put Abraham to the test, saying to him, “Abraham.” He answered, ”Hineni”, Here I am. What was the test?…. The binding of Isaac. God instructs Abraham to go up to mount Moria to sacrifice his son Isaac. Furthermore, Isaac is the son that God had promised would continue Abraham’s lineage and legacy when his progeny become the Jewish people. Abraham agrees to carrying out the sacrifice. But at the last moment God stops Abraham from actually executing, literally and figuratively, and Isaac’s life is spared. God then pronounces: ...כִּ֣י ׀ עַתָּ֣ה יָדַ֗עְתִּי כִּֽי־יְרֵ֤א אֱלֹהִים֙ אַ֔תָּה וְלֹ֥א חָשַׂ֛כְתָּ אֶת־בִּנְךָ֥ אֶת־יְחִידְךָ֖ מִמֶּֽנִּי׃ (בראשית כ״ב, יב) “now I know that you fear Elohim”, (your obedience has been proven). If there ever was a test, this one tops them all, doesn’t it? Why does God test Abraham? Why does God test any of us? What is the purpose of the test, the desired outcome? Is this simply a test of faith as the narrative suggests, or is there more? What can it teach us about the tests we are experiencing right now in Israeli society and politics? What can it teach us about our own personal tests and travails? Rashi offers two possible explanations to why God decided to test Abraham: … “Of all the banquets (to celebrate the weaning of Isaac) which Abraham had prepared, not a single bull nor a single ram did he bring as a sacrifice to You (says Satan). God replied to him: Does he do anything at all except for his son (Isaac’s) sake? Yet if I were to ask him: Sacrifice him (Isaac) to Me, he would not refuse’’ (Tractate Sanhedrin 89b). Second explanation, “... Ishmael... boasted to Isaac that he had been circumcised when he was thirteen years old without resisting. Isaac replied to him: You think to intimidate me by mentioning the loss of one (small) part of the body! If the Holy One, blessed be He, were to tell me, ‘Sacrifice yourself to Me’ I would not refuse” (Tractate Sanhedrin 89b). רשי אחר הדברים האלה. יֵשׁ מֵרַבּוֹתֵינוּ אוֹמְרִים (סנהדרין פ"ט) אַחַר דְּבָרָיו שֶׁל שָׂטָן, שֶׁהָיָה מְקַטְרֵג וְאוֹמֵר מִכָּל סְעוּדָה שֶׁעָשָׂה אַבְרָהָם לֹא הִקְרִיב לְפָנֶיךָ פַּר אֶחָד אוֹ אַיִל אֶחָד; אָמַר לוֹ כְּלוּם עָשָׂה אֶלָּא בִּשְׁבִיל בְּנוֹ, אִלּוּ הָיִיתִי אוֹמֵר לוֹ זְבַח אוֹתוֹ לְפָנַי לֹא הָיָה מְעַכֵּב; וְיֵ"אֹ אַחַר דְּבָרָיו שֶׁל יִשְׁמָעֵאל, שֶׁהָיָה מִתְפָּאֵר עַל יִצְחָק שֶׁמָּל בֶּן י"ג שָׁנָה וְלֹא מִחָה, אָמַר לוֹ יִצְחָק בְּאֵבֶר א' אַתָּה מְיָרְאֵנִי? אִלּוּ אָמַר לִי הַקָּבָּ"ה זְבַח עַצְמְךָ לְפָנַי, לֹא הָיִיתִי מְעַכֵּב. A Midrash in Bereshit Rabbah (55:1) offers another explanation: “… It is written (in the Psalms [60:6]), ‘You have given a Nes (flag, banner) to those who fear You, that it may be displayed [lehithnoses] because of truth [koshet]…’. (What does the Psalm mean?) This means, trial after trial, greatness after greatness, in order to test (Nisa) them... and exalt them in the world like a ship’s flag. And why all this? … so that the attribute of (courage to do) justice [din] may be... (established)... in the world…. If you ask…: ‘Can you do what Avraham did?’… (as) it was said to him: ‘Take, please, your son, your only son’ (22:2), yet he did not refuse. This is (the meaning of) ‘You have given a flag to those who Fear You (or have courage to follow Your ways of justice), that it may be displayed’. בראשית רבה נ״ה:א׳ וַיְהִי אַחַר הַדְּבָרִים הָאֵלֶּה וְהָאֱלֹהִים נִסָּה אֶת אַבְרָהָם (בראשית כב, א), כְּתִיב (תהלים ס, ו): נָתַתָּה לִּירֵאֶיךָ נֵס לְהִתְנוֹסֵס מִפְּנֵי קשֶׁט סֶלָּה, נִסָּיוֹן אַחַר נִסָּיוֹן, וְגִדּוּלִין אַחַר גִּדּוּלִין, בִּשְׁבִיל לְנַסּוֹתָן בָּעוֹלָם, בִּשְׁבִיל לְגַדְּלָן בָּעוֹלָם, כַּנֵּס הַזֶּה שֶׁל סְפִינָה. וְכָל כָּךְ לָמָּה, מִפְּנֵי קשֶׁט, בִּשְׁבִיל שֶׁתִּתְקַשֵּׁט מִדַּת הַדִּין בָּעוֹלָם, שֶׁאִם יֹאמַר לְךָ אָדָם לְמִי שֶׁהוּא רוֹצֶה לְהַעֲשִׁיר מַעֲשִׁיר, לְמִי שֶׁהוּא רוֹצֶה מַעֲנִי, וּלְמִי שֶׁהוּא רוֹצֶה הוּא עוֹשֶׂה מֶלֶךְ, אַבְרָהָם כְּשֶׁרָצָה עֲשָׂאוֹ מֶלֶךְ, כְּשֶׁרָצָה עֲשָׂאוֹ עָשִׁיר, יָכוֹל אַתְּ לַהֲשִׁיבוֹ וְלוֹמַר לוֹ יָכוֹל אַתְּ לַעֲשׂוֹת כְּמוֹ שֶׁעָשָׂה אַבְרָהָם אָבִינוּ, וְהוּא אוֹמֵר מֶה עָשָׂה, וְאַתְּ אוֹמֵר לוֹ (בראשית כא, ה): וְאַבְרָהָם בֶּן מְאַת שָׁנָה בְּהִוָּלֶד לוֹ, וְאַחַר כָּל הַצַּעַר הַזֶּה נֶאֱמַר לוֹ (בראשית כב, ב): קַח נָא אֶת בִּנְךָ אֶת יְחִידְךָ וְלֹא עִכֵּב, הֲרֵי נָתַתָּה לִּירֵאֶיךָ נֵס לְהִתְנוֹסֵס. This Rabbi doubts that Abraham’s test was about Satan’s challenge, nor due to a teenage argument between Isaac and Ishmael about who is braver. Was the test about promoting courage to follow justice? Perhaps. But most likely, more than anything else, it was about Abraham’s unyielding hope against all odds. Let me explain. Throughout this ordeal Abraham never forgets or ceases to believe in his original purpose, which is to “be a blessing”…. He never ceases believing the original and formative message he received early on, that God’s ultimate nature is blessing. As we read in Parashat Lekh Lekha: ב וְאֶֽעֶשְׂךָ֙ לְג֣וֹי גָּד֔וֹל וַאֲבָ֣רֶכְךָ֔ וַאֲגַדְּלָ֖ה שְׁמֶ֑ךָ וֶהְיֵ֖ה בְּרָכָֽה׃ I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you; I will make your name great, and you shall be a blessing. ג וַאֲבָֽרְכָה֙ מְבָ֣רְכֶ֔יךָ וּמְקַלֶּלְךָ֖ אָאֹ֑ר וְנִבְרְכ֣וּ בְךָ֔ כֹּ֖ל מִשְׁפְּחֹ֥ת הָאֲדָמָֽה׃ (פרשת לך לך בראשית יב: 2,3) I will bless those who bless you, and curse the one who curses you; And all the families of the earth, shall bless themselves by you.” What a powerful and hopeful message?! The core of Abraham’s covenant with God has entirely to do with “being a blessing”, as is God. Thus, Abraham is conscious of the original truth about God, even though it seems hidden behind the veneer of an awful test. The truth that God is “Blessing” and the source of hope. He remembers at every moment that God’s overarching essence is Blessing… blessing for Isaac… blessing for Abraham… blessing for all of humanity. Abraham knew that inside a mind-boggling, soul torturing test, there was concealed a God of hope. Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Leiner of Izhbitz author of Mei HaShiloah illustrates this idea very beautifully. He asks, who exactly is Abraham demonstrating faith in? He points to God’s response at the end of the test: “...now I know that you fear Elohim”. Abraham is obedient specifically to Elohim, not to Adonai... in other words, Abraham may have demonstrated obedience to Elohim, but was ultimately faithful only to Adonai. Elohim and Adonai are not the same according to the sages. Elohim is the challenging and testing aspect of God. The aspect to be feared. But Adonai is the God aspect of compassion, blessing, and hope, which according to the sages, supersedes everything else. The stubborn adherence to this principle, that compassion, blessing, and hope supersede all challenges was Abraham’s greatness. He believed in hope above all, even when called to obey from fear. And so do we. As a Jewish people, we have endured many tests over the centuries, from without and from within, yet we clung to hope. That is why we are still here to tell the story. These days of political and social turmoil we are being tested again, primarily from within. Our systems of governance, our very democracy are facing an unprecedented crisis. As a society we are disagreeing about the fundamental rules of the game. We are dangerously divided. We need to take decisive actions in order to resolve the crisis, there is no choice. The process is stressful and frightening. Yet, especially today on Rosh HaShanna, we remember that we are ultimately here, in this test, in order to tell Abraham’s story, a story of unyielding hope against all odds. It is not even an option, telling the story of resilience through hope is in our DNA… it defines our Jewish mission. There will be a hopeful ending to this test as well. In our private lives too, health challenges, family challenges, work challenges, spiritual challenges, we need to seek help and find solutions but also, like Abraham, we must cling to hope. Hope is Adonai’s essence … and Adonai’s expectation of us. This is why today’s Haforah ends with the famous verse from Jeremiah: הֲבֵן֩ יַקִּ֨יר לִ֜י אֶפְרַ֗יִם, אִ֚ם יֶ֣לֶד שַׁעֲשֻׁעִ֔ים, כִּֽי־מִדֵּ֤י דַבְּרִי֙ בּ֔וֹ זָכֹ֥ר אֶזְכְּרֶ֖נּוּ ע֑וֹד, עַל־כֵּ֗ן הָמ֤וּ מֵעַי֙ ל֔וֹ, רַחֵ֥ם אֲֽרַחֲמֶ֖נּוּ, נְאֻם־יְהֹוָֽה׃ (הפטרה ליום ב’ ראש השנה ירמיהו ל״א כ) “Truly, Ephraim (a euphemism for Israel) is a dear son to Me (Adonai). A child that is dandled! Whenever I have turned against him, My thoughts (Adonai’s thoughts) would dwell on him still. That is why My heart yearns for him; I will receive him back in love, declares Adonai.” I started my comments with the verse from today’s Torah reading: וְהָ֣אֱלֹהִ֔ים נִסָּ֖ה אֶת־אַבְרָהָ֑ם וַיֹּ֣אמֶר אֵלָ֔יו אַבְרָהָ֖ם וַיֹּ֥אמֶר הִנֵּֽנִי׃(בראשית כ״ב, יב) “God put Abraham to the test, saying to him, “Abraham.” He answered, “Hineni”, I am ready, because I am full of hope. Are we? Shanah Tovah U’Metukah 1+ 80 + 200 + 10 + 40 = 331 אפרים 7 60 + 30 + 10 + 8 + 5 = 133 סליחה 7 300 + 6 + 2 + 5 = 313 שובה 7 400 + 100 + 6 + 5 = 511 תקוה 7  על הניכור החילוני דתי והדמוקרטיה הישראלית Click here for the English version החברה הישראלית יהודית מאפשרת לדתיים הקיצוניים שליטה בנכס הלאומי המשותף לכולנו - תורת ישראל. שמעתי בהפגנת מחאה דובר מסורתי אומר: ״הדתיים הקיצוניים גנבו לנו את התורה ועלינו לגנוב אותה מהם בחזרה״. איך זה קרה? ראש הממשלה דוד בן גוריון מסר את ניהולם של נישואים, גירושים, קבורה, גיור, וכדומה בידי הרבנות הראשית המנוהלת על ידי המיעוט האורתודוקסי. הדרישות הפרקטיות של בנית מדינה היו בראש סדר העדיפויות של המנהיגים דאז ולכן הבטחת נציגות הולמת לכל זרמי היהדות בעניני ״דת״ נדחתה למועד מאוחר יותר. כך קובעה השפעתם של האורתודוקסים על עיצוב הזהות היהודית של הפרט ושל המדינה והחל תהליך של ניכור בין חילוניים ודתיים. ניכור חברתי ופסיכולוגי זה הוא לדעתינו גורם מרכזי המניע את מאות אלפי הישראלים למחאה סוערת כבר שבועות רבים. שלושה אופנים לניכור. האופן הבולט ביותר הוא הניכור בין חרדים לחילוניים היוצר שפוטיות, וכעס הדדיים. שנית ישנו ניכור פנים-חילוני. זהו כשל חילוני במיזוג משמעותי של ערכי היהדות והדמוקרטיה. אלה שוחים בנוחות בדמוקרטיה האוניברסלית, אך בורים ונבוכים בנושא זהותם היהודית. חילוניים קיצוניים לעיתים אפילו קוראים בשאט נפש למחיקה מוחלטת של הזהות היהודית. השלישי הוא ניכור פנים-דתי. הכשל החרדי הוא לראות את הזימון ההיסטורי עם הקמת מדינת ישראל לשינוי וצמיחה בעולמה של היהדות. הם מנוכרים מהמדינה המודרנית תוך אחיזה בעבר הגלותי. הם החליפו מעשיות וגמישות יהודית בהזיות אמונוית. החרדים שוכחים שהבורא ״מחדש בטובו בכל יום תמיד מעשה בראשית״ (זוהר פקודי נב) ונכשלים באהבת (כל) ישראל ובענווה הנדרשת לכך. פיתויי הרווחה החומרית, החופש, והנאורות של העולם המערבי גורמים לאדם החילוני לדחות על הסף את התורה ומגבלותיה-לכאורה. כתוצאה החילוניים מזניחים את תפקידם בעיצוב זהותה היהודי של המדינה. הפחד מפני המודרניות גורמים לאדם הדתי להשקיע את מלוא משאביו בהגנה מפני ההשפעות השליליות-לכאורה של החילוניות. כתוצאה, הוא שואף למדינה במתכונת תנכית. חילוניות לבדה מתכחשת לשורשיה היהודיים של ישראל. דתיות לבדה מיצרת הזיות תלושות ומסוכנות. גם הדתיים וגם החילוניים מנוכרים מהמציאות של תלותם ההדדית כאשר כל צד זקוק לשני להשלים ישראליות ראויה. הרמבם כותב: ״וְאָמְנָם יְשֻׁבַּח בֶּאֱמֶת הַמְמֻצָּע, וְאֵלָיו צָרִיךְ לָאָדָם שֶׁיְּכַוֵּן וְיִשְׁקֹל פְּעֻלּוֹתָיו כֻּלָּם תָּמִיד עַד שֶׁיִּתְמַצְעוּ.״ (שמונה פרקים). הוא מלמד שהגות והתנהגות נכונים נמצאים במרכז שבין הקצוות. במרכזה של הפוליטיקה הישראלית מתמזגים בנוחות דמוקרטיה ותורה - זהות יהודית שורשית עם שיטת ממשל מסודרת וישרה. נראה שהמחאה יצרה בין השאר קרקע דשנה בה צומחת משנה של מרכז ישראלי יהודי בונה. לכן הסופר יוסי קליין הלוי אמר לאחרונה ש״ישראל היום מצויה במאבק כוחות בין המרכז והימין על הגדרת המשמעות של המונחים מדינה יהודית ומדינה דמוקרטית.״ (מכון הרטמן) בלילה קייצי לח בעיר פילדלפיה בשנות ה90 המוקדמות ניהלתי שיחה עם שכני דאז הרב דר. ארטור גרין, פרופסור ללמודי יהדות ומחבר של סידרת ספרי תאולוגיה. בזמנו הייתי ישראלי חילוני צעיר שירד מהארץ עם חור בהשכלה היהודית ורגשי עוינות כלפי הדת היהודית ונציגיה. הרב גרין הסביר ש״עתידה של היהדות תעוצב בעיקר בידי הקהילה החילונית הישראלית ולא בידי המסורות הגלותיות הישנות. ושהמסורות הישנות יתמוססו במשך הזמן בעוד מסורות חדשות הנמשכות מחווית חיינו העכשוית, תצמחנה ותעצבנה את חיי עם ישראל אל תוך העתיד.״ רעיונתיו של הרב גרין בזמנו היו מעל ומעבר לתפיסתי. לא יכולתי לדמיין לעצמי יהודים השונים מחובשי הכיפות השחורות וחובשות השייטלס שהיו מוכרים.ות לי היטב מן המולדת. ״ישראלים חילוניים מנוכרים, מבולבלי זהות השונאים את הממסד הדתי יעצבו את העתיד היהודי? בלתי אפשרי!״ סיכמתי לעצמי. כשלושים שנה מאוחר יותר, בעיצומה של המחאה הדמוקרטית, החזון של הרב גרין מתחיל להסתמן כממשות. נראה היום שהמחאה מאותתת לקהל החילוני והמסורתי במרכז לקחת אחריות על היהדות והישראליות תוך מציאת האמצע בין הקצוות. שתי הנחות יסוד רדיקליות מניעות את המרכז הישראלי המתגבש. האחת, שהמודרניות והחילוניות אינן עומדות בסתירה לתורת ישראל, הליבה ההיסטורית של הזהות היהודית והישראלית. דרך מסורת הפרשנות היהודית, התורה ממשיכה להיות רלוונטית בדורנו ובמצבינו כפי שהיא הייתה בכל דור ודור. ההנחה הרדיקלית השניה היא שהשליטה האורתודוקסית על פרשנות התורה ועל התוויית החיים היהודיים בישראל היא שגויה בעליל. נכון לעכשיו השליטה האורתודוקסית והכפיה הדתית גרמו לניכור בלתי נסבל ונזק עמוק לעם ישראל. אורתודוקסים וחילוניים, מסורתיים והומניסטים, רפורמים ואחרים יכולים וצריכים לעצב את הזהות היהודית והדמוקרטית של המדינה בשותפות שוויונית והדדית. במגילת העצמאות כתוב: “זו זכותו הטבעית של העם היהודי להיות ככל עם ועם עומד ברשות עצמו במדינתו הריבונית.״ האם משמעות האימרה ״להיות ככל עם ועם״ היא לחקות את דנמרק, למשל, והדמוקרטיה הנאורה שלה? או לחלופין האם ״ככל עם״ פרושו לבטא את זהותנו היחודית כמו שכל עם מבטא את זהותו ויחודיותו. לדעתנו ריבונותו של העם היהודי, מהגדרתו ומטבעו ,הוא שילטון דמוקרטי המושתת על הערכים והחכמה המעוגנים בתורה ובמסורת ישראל. עקרונות היסוד של הדמוקרטיות המערביות, צדק והגינות, דיון ושכנוע, שימור זכויות המיעוט, מיגבלות על הרשות המבצעת, והכרעה על פי רוב, מעוגנות במילא בתורת ישראל ומסורת הפרשנות. אנו קוראים בספר דברים: שֹׁפְטִ֣ים וְשֹֽׁטְרִ֗ים תִּֽתֶּן־לְךָ֙ ... וְשָׁפְט֥וּ אֶת־הָעָ֖ם מִשְׁפַּט־צֶֽדֶק׃ (16:18) לֹא־תַטֶּ֣ה מִשְׁפָּ֔ט לֹ֥א תַכִּ֖יר פָּנִ֑ים (16:19) צֶ֥דֶק צֶ֖דֶק תִּרְדֹּ֑ף לְמַ֤עַן תִּֽחְיֶה֙ (16:20) וְאָמַרְתָּ֗ אָשִׂ֤ימָה עָלַי֙ מֶ֔לֶךְ כְּכָל־הַגּוֹיִ֖ם אֲשֶׁ֥ר סְבִיבֹתָֽי׃ (17:14) רַק֮ לֹא־יַרְבֶּה־לּ֣וֹ סוּסִים֒... (17:16) וְלֹ֤א יַרְבֶּה־לּוֹ֙ נָשִׁ֔ים... וְכֶ֣סֶף וְזָהָ֔ב לֹ֥א יַרְבֶּה־לּ֖וֹ מְאֹֽד׃ (17:17) וְהָיָ֣ה כְשִׁבְתּ֔וֹ עַ֖ל כִּסֵּ֣א מַמְלַכְתּ֑וֹ וְכָ֨תַב ל֜וֹ אֶת־מִשְׁנֵ֨ה הַתּוֹרָ֤ה הַזֹּאת֙ עַל־סֵ֔פֶר… (17:18) ...וְקָ֥רָא ב֖וֹ... לִ֠שְׁמֹר אֶֽת־כָּל־דִּבְרֵ֞י הַתּוֹרָ֥ה הַזֹּ֛את וְאֶת־הַחֻקִּ֥ים הָאֵ֖לֶּה לַעֲשֹׂתָֽם׃ (17:19) לְבִלְתִּ֤י רוּם־לְבָבוֹ֙ מֵֽאֶחָ֔יו וּלְבִלְתִּ֛י ס֥וּר מִן־הַמִּצְוָ֖ה יָמִ֣ין וּשְׂמֹ֑אול… (17:20) אנחנו קוראים בספר ויקרא: לֹֽא־תִקֹּ֤ם וְלֹֽא־תִטֹּר֙ אֶת־בְּנֵ֣י עַמֶּ֔ךָ וְאָֽהַבְתָּ֥ לְרֵעֲךָ֖ כָּמ֑וֹךָ… ׃(19:18) וְכִֽי־יָג֧וּר אִתְּךָ֛ גֵּ֖ר בְּאַרְצְכֶ֑ם לֹ֥א תוֹנ֖וּ אֹתֽוֹ׃ (19:33) כְּאֶזְרָ֣ח מִכֶּם֩ יִהְיֶ֨ה לָכֶ֜ם הַגֵּ֣ר הַגָּ֣ר אִתְּכֶ֗ם וְאָהַבְתָּ֥ לוֹ֙ כָּמ֔וֹךָ כִּֽי־גֵרִ֥ים הֱיִיתֶ֖ם בְּאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרָ֑יִם (19:34) התורה מורה לנו לבסס מערכת משפטית המתפקדת תחת כללי צדק מפורטים. להגביל את המערכת המבצעת על ידי חוקה. ולתת לגרים בתוכינו זכויות, שוויון, ואהבה. על פי מסורת ישראל שיטת המימשל היא ציווי אלוהי. אבל המשילה ניתנה לבני אדם. אנו קוראים בספר דברים: כִּ֚י הַמִּצְוָ֣ה הַזֹּ֔את… לֹֽא־נִפְלֵ֥את הִוא֙ מִמְּךָ֔ וְלֹ֥א רְחֹקָ֖ה הִֽוא׃ לֹ֥א בַשָּׁמַ֖יִם הִ֑וא לֵאמֹ֗ר מִ֣י יַעֲלֶה־לָּ֤נוּ הַשָּׁמַ֙יְמָה֙ וְיִקָּחֶ֣הָ לָּ֔נוּ וְיַשְׁמִעֵ֥נוּ אֹתָ֖הּ וְנַעֲשֶֽׂנָּה׃ כִּֽי־קָר֥וֹב אֵלֶ֛יךָ הַדָּבָ֖ר מְאֹ֑ד… לַעֲשֹׂתֽוֹ׃ (30:11,12,14) התלמוד הבבלי ממשיך ומפתח את העקרונות הדמוקרטיים של דיון, שיכנוע, והכרעה על פי הרוב. התלמוד מספר על מליאה של רבנים הדנים בכשרותו של תנור. פסיקתו של הרב אליעזר הייתה לחיוב, אך הרוב ובראשם רבי יהושע פסקו לשלילה. הרב אליעזר ביקש שמין השמיים יוכיחו את צדקת פסיקתו ואכן בת קול יצאה מין השמיים והכריזה שהלכה כדברי רבי אליעזר. אך למרות הסיוע ״עמד רבי יהושע על רגליו... (וציטט) ’לא בשמים היא’ (דברים ל, יב)…. (למה) לא בשמים היא? אמר רבי ירמיה, (מכיוון) שכבר נתנה תורה מהר סיני אין אנו… (שומעים) בבת קול, שכבר כתבת (אלוהים)... בתורה ’אחרי רבים להטות’ (מכריעים על פי רוב)(שמות כג:ב). ...(שאל) רבי נתן לאליהו (הנביא)... (מה עשה הקדוש ברוך הוא באותה שעה)? אמר לו (אליהו הנביא),... (אלוהים) חייך ואמר ’נצחוני בני נצחוני בני’.״ (בבא מציעא נ״ט: ) כשחורזים את הפסוקים מספר דברים, ויקרא, ופרשנות התלמוד אנו לומדים על שיטת מימשל הכוללת שלוש רשויות: שופטת, מבצעת, ומחוקקת. על הרשות השופטת לשפוט על פי חוקי הצדק. על הרשות המבצעת לפעול אך ורק בתוך מגבלות החוקה. על הרשות המחוקקת לדון על פי שיקולים אנושיים, לא להטות אחר ניסים ונפלאות, ולהכריע על פי דעת הרוב. העקרונות של מימשל תקין ודמוקרטי נכללו בתורה ונדונו במסורת הפרשנות לפני שאתונה ורומא חידשו את חידושיהם. צדק וסדר חברתי לא היו חדשים לאבותינו ולאמהותינו, נהפוך הוא. באמתחתינו, מסורת מתוחכמת המתאימה יחודית לריבונתה ואופיה של ישראל המודרנית. בכדי לממש בהצלחה מלאה את ההבטחה של מגילת העצמאות, ובכדי שהמימשל בישראל יתקבל באהבה על ידי רוב העם, על השיטה המשטרית לינוק ממהותה הרוחנית של עם ישראל. עלינו, דתיים וחילוניים, שמאלנים וימניים לנצל במלואם את נכסינו התרבותיים וההיסטוריים לבניית דמוקרטיה תקינה וראויה ולשם כך עלינו לפורר את דפוסי הניכור הזהותי אשר אפיינו אותנו עד הלום. הוערנו בטלטלה על ידי ההפיכה המשטרית והוטלנו אל תוך מלחמת עצמאות שניה על נשמתה של המדינה. לכן על המרכז הישראלי להטות שכם ביחד ובחוזקה למען התכלית והעתיד של עם ישראל. תכלית זו כוללת בתוכה בניית דמוקרטיה לדוגמא. מגילת העצמאות מבטיחה חופש וצדק לכל אזרחי ישראל ״דתיים וחילוניים, ימנים ושמאלנים, יהודים וערבים, ועוד״. אך היא לא מגילת העצמאות הראשונה של עם ישראל, אלא השניה. המגילה הראשונה, התורה, ציינה את היציאה מעבדות לחרות ואת המשימה הלאומית להיות עם חופשי בארץ האבות והאמהות. כשאנו מפגינים כל שבוע בכדי למגר את ההפיכה השילטונית אנחנו מקדשים את ערכי היסוד המשותפים של עם ישראל הרשומים בשתי המגילות, העתיקה והחדשה. השלום והביטחון, הרווחה, והצביון של מדינת ישראל תלויים במלחמתנו למען שתיהן בחוסן ובאהבה.  The First Scroll, Israeli Democracy and the Secular Religious Impasse To read the Hebrew version click here. Early on when the modern state of Israel was founded, Israeli society has enabled the extreme Jewish religious right to assume legal and cultural control over our people’s most cherished collective possession, the Torah. Recently I heard a moderate religious speaker at a pro-democracy rally express the sentiment, “they (the religious right) stole our Torah and we need to steal it back from them.” How did it happen? Then prime minister, David Ben Gurion, entrusted matters of legal Jewish status and law, such as marriage, divorce, burial, conversion, sacred text study, and more, into the hands of an Orthodox state rabbinate. The practical urgencies of building and protecting the new state dominated the leaders’ agenda. As a result, ensuring equal representation for the entire range of Jewish faith styles, and ideological world views where put on the back burner thus solidifying the Orthodox minority’s power over shaping Jewish identity and the Jewish character of the state. This created deep alienation among the religious and secular extremes. We believe that this social and psychological alienation are a core factor energizing hundreds of thousands of Israelis to fiercely protest week after week. Let’s take a close look at the religious/secular alienation dynamics. The first and most conspicuous is the alienation between the Orthodox and secularists in the form of mutual judgments and animosity. The second is inter-secular. Secular persons are alienated from their very own Jewish identities. They have failed to fully and coherently blend their Jewish and democratic values. In the secularist camp people are typically more fluent within the universalist democracy space but are too often ignorant about the Jewish identity space. Extreme secularists in Israel often call for abandoning Jewish identity altogether. The third is inter-traditionalist. Stuck in defending the Jewish traditions of the past, ultra-traditionalists are alienated from this historical moment’s demand for change. They seem alienated from modern Israel while cleaving to a diaspora past. Traditionalists have forgotten that Adonai is “The One who renews the act of creation... everyday and forever ” הַמְחַדֵּשׁ בְּטוּבוֹ בְּכָל יוֹם תָּמִיד מַעֲשֵׂה בְרֵאשִׁית (Zohar Pedukei 52). Often the Israeli rabbinate is divorced from genuine “Love of (all of) Israel” and the basic humility that it requires. Most secularists, seduced by the material as well as intellectual temptations of modernity, fend off the seemingly restricting influences of Torah as they neglect to fully take responsibility for their own as well as their country’s Jewish identity. Most traditionalists, critical of, and scared by, modernity invest much of their energies in fending off the seemingly negative influences of secularism attempting to shape Israel into a biblical fantasyland. To date the Orthodox hegemony along with its religious coercion has caused enormous alienation and untold damage to the Jews of modern Israel as well as to Jews abroad. Secularism alone denies Israel’s Jewish roots and raison d'être. Tradition alone can produce dangerously fanatical fantasies. Both traditionalists and secularists are alienated from their inevitable interdependency. Each side needs the other, as together we are parts of a greater Israeli whole. Rambam (Maimonides) coined the terms “The Golden Mean”. He writes וְאָמְנָם יְשֻׁבַּח בֶּאֱמֶת הַמְמֻצָּע,וְאֵלָיו צָרִיךְ לָאָדָם שֶׁיְּכַוֵּן וְיִשְׁקֹל פְּעֻלּוֹתָיו כֻּלָּם תָּמִיד עַד שֶׁיִּתְמַצְעוּ. “And indeed the middle way is best, towards which a person should aim in his/her conduct always until it reaches the middle.” (Eight Chapters). He teaches that correct ideation and conduct is found in the center between the extremes. The Center of Israeli politics and Israel’s society is where Torah and democracy - rooted Jewish identity and best governing practices - are merging. The pro-democracy protests have become the petri dish in which a strong center is finding its voice. As the Israeli writer Yossi Klein Halevi said at a recent speech “Israel today is living through a dispute between the center and the right over what a Jewish state and a democratic state mean…” (Hartman Institute, Jerusalem). On a warm and humid summer night back in Philadelphia in the early 1990s I had a long conversion with my neighbor, Rabbi Dr. Arthur Green. He, a published author, Jewish theologian, and professor of Jewish studies. I, a young secular Israeli and recent Yored (immigrant from Israel) with an enormous gap in Jewish knowledge and intense negative feelings toward Jewish religion and its Orthodox emissaries. Rabbi Green, who used to spend a good portion of each year immersing in the Israeli zeitgeist, explained that “The future of Judaism is being shaped primarily by the secular community in Israel, not by the diaspora religious traditions. The old-time traditions are going to wither-on-the-vine while a new form of Judaism, authentic to our times, emerges”. To me, Rabbi Green’s ideas were beyond comprehension at the time. I could not imagine a Judaism looking much different than the yarmulka bearing, black suited men and Sheitel (religious head covering) wearing women I knew from back home. “Alienated secular Israelis with their wrenching identity conundrums and intense hate of the religious establishment, having a constructive role in Judaism’s future? Impossible!”, I thought. Now, thirty years hence, with energetic democracy protests all over Israel, Rabbi Green’s vision is manifesting, bridging the Israeli alienation gap and reviving the Israeli center. Two radical assumptions are animating this center. The first assumption is that Torah is not antithetical to modernism and secularism. To the contrary it is undeniably the core of our Jewish and Israeli identity. The second radical assumption is that the long entrenched hegemony of Orthodoxy over Torah interpretation and over shaping Jewish lifestyles in Israel is categorically wrong. In a healthy center, Orthodox, Secular, Conservative, Humanist, Reform, and Other will collaboratively draw the contours of Israel’s Jewish and democratic identity. “The Jewish people possess a natural right to be a nation like all nations who control their own destiny in their own sovereign state” (Israel’s Scroll of Independence). “זו זכותו הטבעית של העם היהודי להיות ככל עם ועם עומד ברשות עצמו במדינתו הריבונית. What is the meaning of “to be a nation like all nations”? Does it mean being like Denmark with her enlightened democracy? Or does it mean expressing our own unique identity and governing solutions just like other nations express theirs? In our opinion, the Jewish sovereign state, by definition, governs itself through an exemplary democracy based on the values and wisdom of Torah and Jewish tradition. Furthermore, the guiding principles of most modern democracies: Justice and fairness, protection for the rights of the minority, legal limitations upon the executive branch, debate and persuasion leading to a vote by majority are instructed in the Torah. The first two chapters of Parashat Shoftim, in the book of Devarim (Deuteronomy) read: שֹׁפְטִ֣ים וְשֹֽׁטְרִ֗ים תִּֽתֶּן־לְךָ֙ בְּכָל־שְׁעָרֶ֔יךָ אֲשֶׁ֨ר יְהוָ֧ה אֱלֹהֶ֛יךָ נֹתֵ֥ן לְךָ֖ לִשְׁבָטֶ֑יךָ וְשָׁפְט֥וּ אֶת־הָעָ֖ם מִשְׁפַּט־צֶֽדֶק׃ Deut. 16:18 - You shall appoint magistrates and officials for your tribes,... and they shall govern the people with due justice. לֹא־תַטֶּ֣ה מִשְׁפָּ֔ט לֹ֥א תַכִּ֖יר פָּנִ֑ים וְלֹא־תִקַּ֣ח שֹׁ֔חַד כִּ֣י הַשֹּׁ֗חַד יְעַוֵּר֙ עֵינֵ֣י חֲכָמִ֔ים וִֽיסַלֵּ֖ף דִּבְרֵ֥י צַדִּיקִֽם׃ Deut. 16:19 - You shall not judge unfairly: you shall show no partiality; you shall not take bribes, for bribes blind the eyes of the discerning and upset the plea of the just. צֶ֥דֶק צֶ֖דֶק תִּרְדֹּ֑ף לְמַ֤עַן תִּֽחְיֶה֙ וְיָרַשְׁתָּ֣ אֶת־הָאָ֔רֶץ אֲשֶׁר־יְהוָ֥ה אֱלֹהֶ֖יךָ נֹתֵ֥ן לָֽךְ׃ Deut. 16:20 - Justice, justice shall you pursue, that you may thrive.... כִּֽי־תָבֹ֣א אֶל־הָאָ֗רֶץ אֲשֶׁ֨ר יְהוָ֤ה אֱלֹהֶ֙יךָ֙ נֹתֵ֣ן לָ֔ךְ וִֽירִשְׁתָּ֖הּ וְיָשַׁ֣בְתָּה בָּ֑הּ וְאָמַרְתָּ֗ אָשִׂ֤ימָה עָלַי֙ מֶ֔לֶךְ כְּכָל־הַגּוֹיִ֖ם אֲשֶׁ֥ר סְבִיבֹתָֽי׃ Deut. 17:14 - If, … you decide, “I will set a king over me, as do all the nations about me,” רַק֮ לֹא־יַרְבֶּה־לּ֣וֹ סוּסִים֒ וְלֹֽא־יָשִׁ֤יב אֶת־הָעָם֙ מִצְרַ֔יְמָה לְמַ֖עַן הַרְבּ֣וֹת ס֑וּס וַֽיהוָה֙ אָמַ֣ר לָכֶ֔ם לֹ֣א תֹסִפ֗וּן לָשׁ֛וּב בַּדֶּ֥רֶךְ הַזֶּ֖ה עֽוֹד׃ Deut. 17:16 - Moreover, he shall not keep many horses or send people back to Egypt to add to his horses,...” וְלֹ֤א יַרְבֶּה־לּוֹ֙ נָשִׁ֔ים וְלֹ֥א יָס֖וּר לְבָב֑וֹ וְכֶ֣סֶף וְזָהָ֔ב לֹ֥א יַרְבֶּה־לּ֖וֹ מְאֹֽד׃ Deut. 17:17 - And he shall not have many wives, lest his heart go astray; nor shall he amass silver and gold to excess. וְהָיָ֣ה כְשִׁבְתּ֔וֹ עַ֖ל כִּסֵּ֣א מַמְלַכְתּ֑וֹ וְכָ֨תַב ל֜וֹ אֶת־מִשְׁנֵ֨ה הַתּוֹרָ֤ה הַזֹּאת֙ עַל־סֵ֔פֶר מִלִּפְנֵ֥י הַכֹּהֲנִ֖ים הַלְוִיִּֽם׃ Deut. 17:18 - When he is seated on his royal throne, he shall have a copy of this Teaching (Torah) written for him.... וְהָיְתָ֣ה עִמּ֔וֹ וְקָ֥רָא ב֖וֹ כָּל־יְמֵ֣י חַיָּ֑יו לְמַ֣עַן יִלְמַ֗ד לְיִרְאָה֙ אֶת־יְהוָ֣ה אֱלֹהָ֔יו לִ֠שְׁמֹר אֶֽת־כָּל־דִּבְרֵ֞י הַתּוֹרָ֥ה הַזֹּ֛את וְאֶת־הַחֻקִּ֥ים הָאֵ֖לֶּה לַעֲשֹׂתָֽם׃ Deut. 17:19 - Let it remain with him and let him read in it all his life, ..., to observe faithfully every word of this Teaching (Torah) as well as these laws. לְבִלְתִּ֤י רוּם־לְבָבוֹ֙ מֵֽאֶחָ֔יו וּלְבִלְתִּ֛י ס֥וּר מִן־הַמִּצְוָ֖ה יָמִ֣ין וּשְׂמֹ֑אול לְמַעַן֩ יַאֲרִ֨יךְ יָמִ֧ים עַל־מַמְלַכְתּ֛וֹ ה֥וּא וּבָנָ֖יו בְּקֶ֥רֶב יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃ Deut. 17:20 - Thus he will not act haughtily toward his fellows or deviate from the Instruction to the right or to the left,.... The Torah is setting limits on both the judiciary and executive branches. These limits are guided by justice, moderation, and a commitment to the people’s common good. Parashat Kedoshim, in the book of VaYikra (Leviticus), offers additional guardrails and foundational principles for just conduct: לֹֽא־תִקֹּ֤ם וְלֹֽא־תִטֹּר֙ אֶת־בְּנֵ֣י עַמֶּ֔ךָ וְאָֽהַבְתָּ֥ לְרֵעֲךָ֖ כָּמ֑וֹךָ אֲנִ֖י יְהוָֽה׃ Leviticus 19:18 - You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against members of your people. Love your fellow as yourself …. וְכִֽי־יָג֧וּר אִתְּךָ֛ גֵּ֖ר בְּאַרְצְכֶ֑ם לֹ֥א תוֹנ֖וּ אֹתֽוֹ׃ Leviticus 19: 33 - When strangers reside with you in your land, you shall not wrong them. כְּאֶזְרָ֣ח מִכֶּם֩ יִהְיֶ֨ה לָכֶ֜ם הַגֵּ֣ר ׀ הַגָּ֣ר אִתְּכֶ֗ם וְאָהַבְתָּ֥ לוֹ֙ כָּמ֔וֹךָ כִּֽי־גֵרִ֥ים הֱיִיתֶ֖ם בְּאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרָ֑יִם אֲנִ֖י יְהוָ֥ה אֱלֹהֵיכֶֽם׃ Leviticus 19: 34 - The strangers who reside with you shall be to you as your citizens; you shall love each one as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt .... In other words, the system of government instructed by Torah serves all the inhabitants of the land applying justice equally to the Jewish majority, the Jewish minority, and to the non-Jew. According to the Torah and to Jewish tradition the Israelite system of government was divinely ordained. However it was not to be divinely executed. Implementation is entirely up to us humans here on earth. כִּ֚י הַמִּצְוָ֣ה הַזֹּ֔את אֲשֶׁ֛ר אָנֹכִ֥י מְצַוְּךָ֖ הַיּ֑וֹם לֹֽא־נִפְלֵ֥את הִוא֙ מִמְּךָ֔ וְלֹ֥א רְחֹקָ֖ה הִֽוא׃ Deut. 30:11 - Surely, this Instruction which I enjoin upon you this day is not too baffling for you, nor is it beyond reach. לֹ֥א בַשָּׁמַ֖יִם הִ֑וא לֵאמֹ֗ר מִ֣י יַעֲלֶה־לָּ֤נוּ הַשָּׁמַ֙יְמָה֙ וְיִקָּחֶ֣הָ לָּ֔נוּ וְיַשְׁמִעֵ֥נוּ אֹתָ֖הּ וְנַעֲשֶֽׂנָּה׃ Deut. 30:12 - It is not in the heavens, that you should say, “Who among us can go up to the heavens and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?” כִּֽי־קָר֥וֹב אֵלֶ֛יךָ הַדָּבָ֖ר מְאֹ֑ד בְּפִ֥יךָ וּבִֽלְבָבְךָ֖ לַעֲשֹׂתֽוֹ׃ Deut. 30:14 - No, the thing is very close to you, in your mouth (ordinary language) and in your heart (mind), to observe it. The Talmud offers an interpertaion of “It is not in the heavens… the thing is very close to you…” that expresses the political principle of ‘deliberative process’ leading to a binding ruling of the legislative majority. In the following Talmudic episode an assembly of rabbis are debating a matter of Kosher law. Rabbi Eliezer, ruled that an object was Kosher, while the majority of the attending rabbis ruled it not Kosher. Rabbi Eliezer uses his spiritual powers to request Heaven’s intervention. Indeed, a Heavenly voice rumbles from on-high declaring Rabbi Eliezer’s ruling correct. At this dramatic moment the speaker for the majority... עמד רבי יהושע על רגליו ואמר (דברים ל, יב) לא בשמים היא מאי לא בשמים היא אמר רבי ירמיה שכבר נתנה תורה מהר סיני אין אנו משגיחין בבת קול שכבר כתבת בהר סיני בתורה (שמות כג, ב) אחרי רבים להטות אשכחיה רבי נתן לאליהו א"ל מאי עביד קוב"ה בההיא שעתא א"ל קא חייך ואמר נצחוני בני נצחוני בני ..."Rabbi Yehoshua stood on his feet and said: It is written (in the Torah): “It is not in heaven” (Deuteronomy 30:12). The Gemara asks: What is the relevance of the phrase “It is not in heaven” in this context? Rabbi Yirmeya says: Since the Torah has already been given at Mount Sinai, we do not regard a Divine Voice, as You (God) already wrote... in the Torah: “After a majority to incline” (Exodus 23:2). Since the majority of Rabbis disagreed with Rabbi Eliezer’s opinion, the Halakha (law) is not ruled in accordance with his opinion. The Gemara adds: Years later, Rabbi Natan encountered Elijah the prophet and said to him: What did the Holy One, Blessed Be, do at that time, when Rabbi Yehoshua issued his declaration? Elijah said to him: The Holy One, Blessed Be, smiled and said: My children have triumphed over Me; My children have triumphed over Me.” (Baba Metzia 59:b) Stringing together these verses from Parashat Shoftim, Parashat Kedoshim, and the Talmud, a teaching emerges instructing us to form a system of government that includes a Judiciary, an executive, and a legislator. The Judiciary shall strictly follow the principles of justice, impartiality and fairness. The executive branch shall function under strict limitations guided by a constitution, the Torah. The legislative body shall use the best of its human deliberative capacity, not spiritual signs and portents, as the majority decides the law. The democratic process has been spelled out in the Torah and her interpretations long before ancient Athens and ancient Rome had experimented with theirs. We, Jewish Israelis, indeed have a sophisticated, wise, and time-honored heritage to draw on. We, Israel’s secular and moderate religious center have been politically awakened by the judicial coup and thrust into a second “war of independence” for the soul if not the body of Israel. For Israeli democracy to be truly sovereign, as the Scroll Of Independence calls for, and for our system to be widely adopted by our people it must be rooted in the soul and deep purpose of the modern state of Israel. The ideological and conceptual framework for Israeli democracy needs to draw on the best assets of our rich Jewish heritage. To that end we must unravel the holding pattern of Israeli alienation and embrace the center where religious and secular alienation dissolves allowing for a renewed Jewish future. It is now time to rally around a new shared mission for modern Israel, which includes modeling for the world an exemplary democracy that extends from the Torah values of diversity, justice, and decency. Megilat HaAtzma’ut, Israel’s Scroll Of Independence commits us to ensuring freedom and justice for all of Israel’s inhabitants, “religious and secular, rightists and leftists, Jewish and Arab, and more.” However, Megilat HaAtzna’ut is the second Scroll Of Independence. The first scroll of independence, the Torah, marked Israel’s liberation from slavery and stated the people’s mission to build a society based on justice and freedom in our ancestral homeland. As we demonstrate weekly in order to quash an extreme rightwing religious takeover we are reclaiming Israel’s core common values that are articulated in both of our Scrolls Of Independence, the ancient one and the recent one. Our nation’s peace and security, our prosperity, and our future depends on reclaiming both with vigor and with love. Part 1